Imagine you’ve been doing something for a long time. I mean, a LONG time. Several decades at least. You’ve become famous (well, notable) for the thing you do, and even when you’ve decided to stop doing that thing or do something else, you still have people coming up to you thanking you for doing the original thing or even asking when you’ll go back to doing it. So what are you meant to do in that kind of situation?

For a lot of people my age, Blink-182 defined our childhood. We heard the band everywhere, bought their albums, went to their shows. Through them and associated concert series like the Warped Tour we became aware of other (sometimes better?) bands, and for a few of us that led to even more niche, underground music in the punk rock scene proper. Blink was on the radio, it was on MTV and Fuse, it dominated the few online spaces available to us (at least until social media, again, made other options attainable). I was a fan of theirs when I was a kid. Their music was fast, it had a juvenile sense of humor, and it was easy to sing along to.

When you’re a kid you lack the developed object permanence to understand that things precede you and will last after you’re gone. This is an idea that you learn as you reach and enter adulthood, and yet still some things remained a mystery to me for an embarrassingly long time. For example: did you know that Blink-182 formed nine months after I was born? I didn’t know that until about a decade ago. Guitarist Tom DeLonge was 16 years old and had just been expelled for public intoxication at Poway High School; bassist Mark Hoppus was 20 and working at a record store in Rancho Bernardo. Their original drummer, Scott Raynor, was even younger than DeLonge or Hoppus at 14. This is the lineup that would go on to record Buddha, Cheshire Cat and Dude Ranch.

Music tastes and trends change. What was popular yesterday might not be popular today, and what’s popular right now might not be so in an hour. A lot of music genres endure through the years, punk being chief among them, but even in punk there are waves of what people want to listen to, want to play. Blink-182 started to feel like a band out of time after their fifth, self-titled album came out. That was coincidentally the last album they pushed for eight years, between 2003 and 2011. In that empty space each of the band members went on to do their own things: DeLonge with Box Car Racer and Angels and Airwaves, Hoppus with (+44), and Barker with a host of other bands, features and production credits in punk, metal, hip-hop and beyond. None of these projects were as successful as Blink-182 was, but that’s just how shit goes sometimes. Plus, nobody could say that the three individual musicians weren’t being true to themselves, at least.

Blink-182’s first five albums: Cheshire Cat, Dude Ranch, Enema of the State, Take off Your Pants and Jacket, and Blink-182, are as good as any other classic band’s discography. Yes, they’re rife with dick jokes, and yes there’s this sense of… eternal summer vacation, for lack of a better term, pervading each of them (except for the back half of that last album in the lineup, which gets more forlorn and moody as you go). But you can look at these albums as a cohesive whole and see a kind of artistic statement being played out. They represented the commercialization and capitalist recuperation of punk rock in a very real sense, but nostalgia isn’t really interested in the ideological ramifications of liking something. I still sometimes put Take off Your Pants and Jacket on and listen to the handful of songs on there that unreservedly, without qualification, slap. Fuck you, I’m doing it right now. There’s nothing you can do about it.

By the time the band decided to come back, there was no need for their services, for their brand of punk. 2011 was the age of the exceedingly earnest pop-punk, defined by bands like The Wonder Years, The Story So Far, Man Overboard and Four Year Strong. This was the age of the AR-15-wielding (at least in their mind), jean-short-wearing, emotional-hardcore-listening, hate-moshing “Defend Pop Punk” fan. Blink-182 was not part of this group of musicians or music-lovers, or at least they weren’t by all accounts. Neighborhoods reflected this disconnect, the gulf between where they were and where they ended up. It was filled with the same kind of anthemic synth-laden stadium rock that DeLonge had been making in Angels and Airwaves, as though the assumption was that they’d be able to return after nearly a decade and fill stadiums again. Interestingly, the songs are also much darker than what had been on their previous albums, more, dear god, “mature” lyrics in the sense that it actually felt like adults were writing them. There are still awkward love songs on the album, and I have no way to account for (or interest in defending) the deeply misogynist “Snake Charmer,” but there is at least an attempt here to reckon with their place in the world.

It wasn’t enough, as evinced by the fact that the band once again broke up following Neighborhoods‘ release. Whatever schism had formed between DeLonge, Hoppus and Barker was wide enough to swallow whole their attempt to bridge it. Blink-182 continued on without the guitarist, who returned to Angels and Airwaves and occasionally doing UFO shit. Alkaline Trio’s Matt Skiba joined the band for the next two albums, California and NINE. Through this reshuffling of personnel, maybe the band was trying to force the evolution of its sound to match what was already on its way out – that “Defend Pop Punk”-ass kind of pop punk. Skiba is an accomplished musician and singer in his own right, but here on California it feels apparent that he’s specifically been instructed to be the “backing vocalist” in addition to guitar duties. Songs like “She’s Out of Her Mind” call out strangely to bands like Teenage Bottlerocket and Masked Intruder. Songs like “No Future,” “Home is Such a Lonely Place” and “Kings of the Weekend” are tonally dissonant from each other and present the listener with a kind of whiplash. It is by far less coherent either lyrically or musically than Neighborhoods or, indeed, any other album the band had put out.

If you listen to the second disc on the deluxe version of California, it’s almost like listening to a missing Alkaline Trio album featuring Hoppus and Barker. The first song on this second disc, “Parking Lot,” is almost attempting to set up an alternate history where Hoppus had grown up with Skiba in Chicago, and it just goes like this for another eleven songs. There’s less of a dissonance present on this half of the package but these songs also weren’t released with the original album and besides, I don’t know that they do anything to add context or deepen the experience of listening to the album.

Between California and NINE, more maturation has taken place, with Apple Music’s description of the album including the hilarious line, “dispatching with dick jokes entirely.” There’s more synths, more electronic beats, more rapping per capita on this album than in any previous Blink-182 album, and you’d be forgiven for thinking that maybe you put on an album of remixes instead of an original work. But no, Blink-182 is still immersed (mired?) in the same songwriting formula that has appeared on these albums forever: lots of low- and mid-tempo anthemic choruses, complex and ponderous drum fills from Barker, and guitar/bass melodies and harmonies that sound like they’re supposed to play at the end of a prom scene in a 90s movie. One point of rupture is worth noting: “Generational Divide,” a straight-ahead hardcore tune consisting of the lyrics “Is it better now? Are we better now? All we needed was a lifeline. We swore we’d be better than the last time. Don’t leave, tell me that you’re alright. I’m not the generational divide.” At once an acknowledgement of their impossible position and an expression of their anxieties around their place in music, maybe. Who knows?

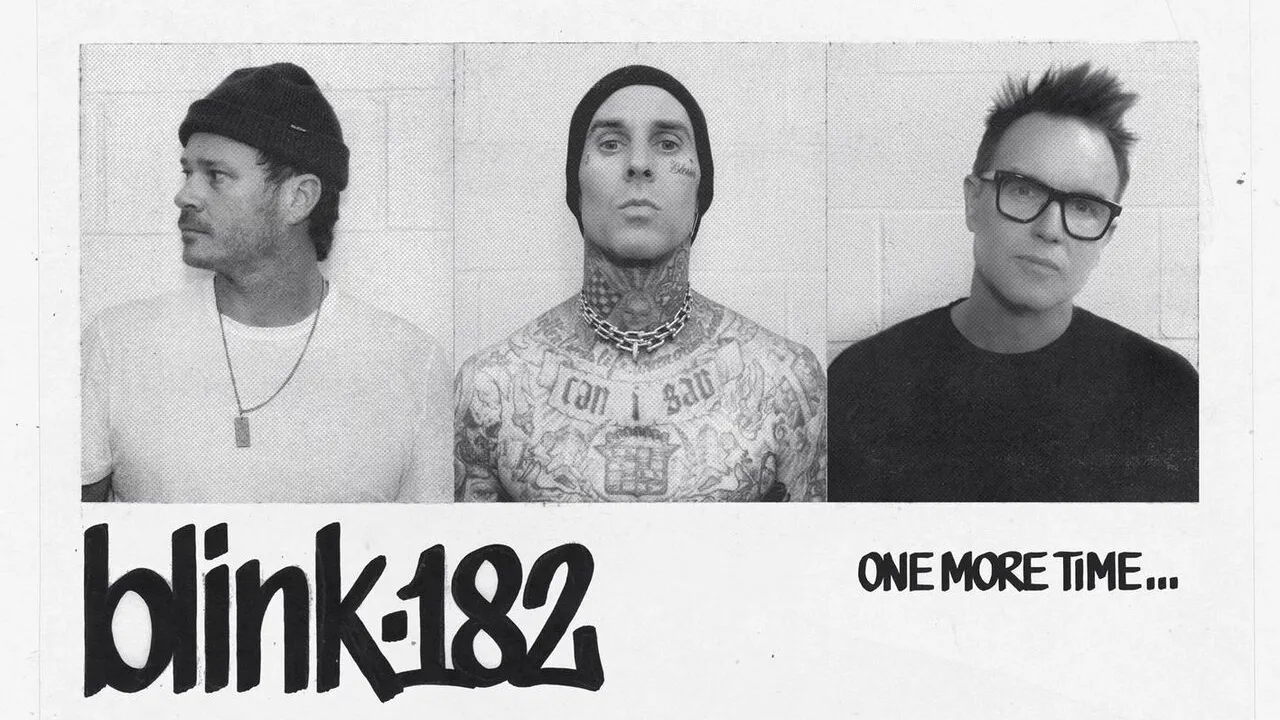

After NINE, Hoppus came down with lymphoma. Somewhere between the initial diagnosis in 2021 and when he was finally cleared and in remission a year later, he and DeLonge managed to reconnect again. Skiba was ejected in 2022 at the same time that DeLonge returned to the band full-time. It’s notable that, on Alkaline Trio’s upcoming album Blood Hair and Eyeballs, on the song of the same name, it starts with the lines, “You showed up and I shut down/ We lost touch and you left town/ You said ‘I never ever wanna see your motherfucking face again.'” Maybe it’s nothing, but it feels like something. Anyway, thank you for reading the previous 1500 words, as all that was preamble to this: 2023, One More Time…, and what might be the true final Blink-182 album ever produced.

NO ESCAPE REVIEWS: BLINK-182 — ONE MORE TIME…

It’s kind of shit, imo. Not worth your time or mine. Go listen to The Menzingers or Teenage Halloween’s new album instead.

Hey did you know that Mark Hoppus has been a libertarian since 2004? Weird, right? Something to think about. Anyway, bye!