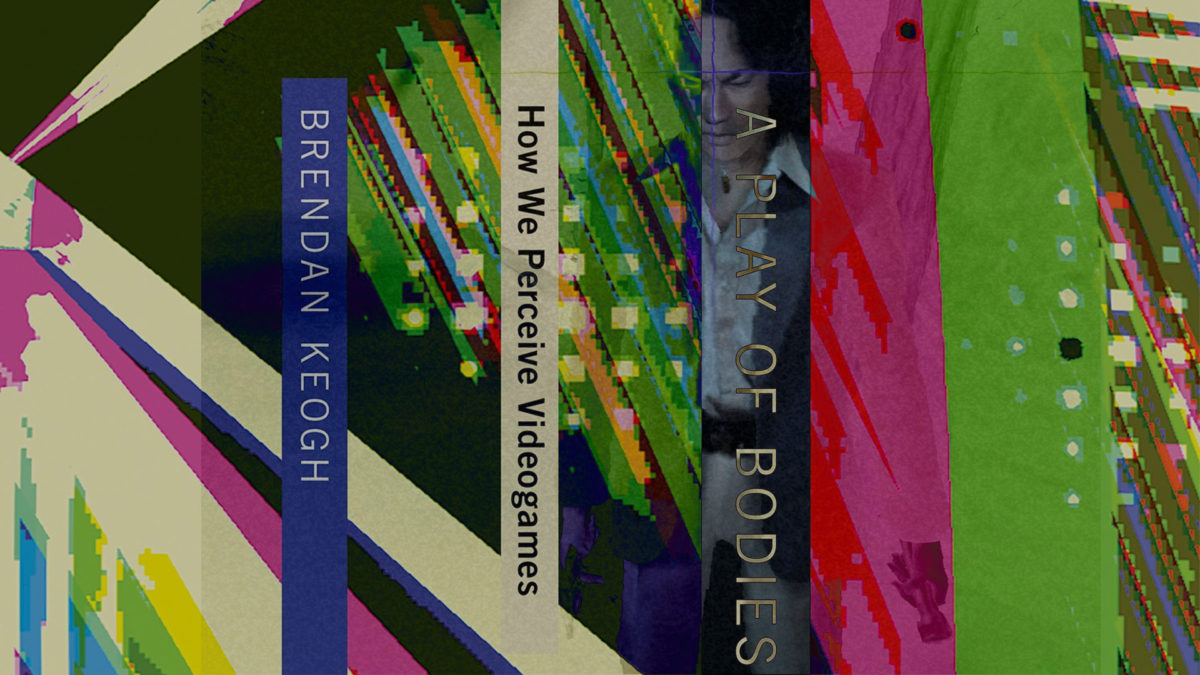

A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames

by Brendan Keogh

MIT Press April 2018 9780262037631

In the background of every videogame experience is the sensation of perceiving its sights and sounds and the inexplicable tactility of how it feels to touch virtual things. But in the rare moment where videogames bring the background to the fore, or when our attention drifts from the drama of videogame stories and their cinematic presentations to the shimmering sensations of vision and movement, isn’t it difficult to describe these feelings, despite their intimate familiarity?

The language to explain a concept like the shape of time in any videogame is elusive, and in my own experience as a player who writes about videogames for both academic and culture crit audiences, the search for a description carrying the same meaning across multiple communities is further complicated by the position I inhabit.

For example, I know a German compound word which could be used to describe how videogames make such sensations accessible and invisible at the same time, like zuhanden, which comes to us English speakers as “ready-to-hand” from the philosophical tradition of phenomenology, the study of the experience of embodied perception. I press down and know the rumble in my palms to mean I have successfully fired a gun because of the representation on the screen and the Zuhandenheit of the triggers on the Dualshock controller.

But as I do this, it feels obvious that the words of 20th century German phenomenologists do not comprise the most ready-at-hand language to describe the way videogames make me feel. I need a language that involves me and my experience, my positionality, my body.

In his recent book A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames, Brendan Keogh has made the compelling case that the difficulty with describing such experiences isn’t so much to do with finding the right words to use, but rather a problem of appreciating the strange form our bodies take on when we play videogames. Keogh’s book addresses a culture embraced by players, game designers, scholars, and critics alike that relegates the consideration of bodily experience to the background, making way for other aesthetic concerns to hold our attention at the fore like narrative or the complexity of mechanics. What goes sadly unappreciated within such a discourse is the fact that videogames rely on bodies; they simply do not work, and thus cannot mean anything, without a body to move and perceive them.

This codependence is the expansive terrain over which Brendan Keogh seeks to trace an image of the videogame playing body in A Play of Bodies. Before we can locate the words to describe the felt sensation of videogames, his book suggests the body we must imagine is one that emerges from the meeting of actual bodies and virtual worlds as a cyborg amalgamation of flesh and machine. This cyborg underscores an ambiguity at the heart of videogame play, where players create effects and are affected in a continuous cycle. Consider this process closely while you play a game, and the hybrid quality of your physical and mental embodiment will become apparent. As cyborgs we augment our normal perceptual abilities, expanding or limiting them; we hold controllers and take up cybernetic appendages letting us feel sight through our thumbs; we spill outside the margins of a normative human form and become what progressive thinkers have called the post-human.

To be a cyborg is not just a poetic metaphor. Playing videogames is strange act of embodiment, which alternates between alienating and empowering. As I read Keogh’s book, I reflected on the many times that I felt as if the controller was a part of my body, a protrusion through which I had gained sensitivity to a new level of perception like a psychic tumor featured in a David Cronenberg movie.

What came to me was a recent memory of using the Sightjack mechanic while playing Siren, a 2003 PlayStation 2 videogame developed by SCE Japan. In the fiction of Siren, player characters are gifted with the psychic ability to see through the eyes of any character in the level, a vital talent for surviving this underrated stealth-horror classic. To use the Sightjack ability I had to press down on the Dualshock’s L2 trigger, immobilizing the player character and bringing me to a full-screen image of television static. From there, I could close the perceptual distance between me and my enemies, hijack their vision and see through their eyes, by radially scanning the area with the left analogue stick in a motion similar to sweeping past static in search of signal with a radio dial. Through just the feeling of this movement alone, distance and proximity between myself and my enemies became an embodied knowledge I could rely on. I remember how it felt as though I could look down at my hands upon the controller and follow the length of my thumb as it trailed into the socket of the analog stick, like the optic nerve of an eye peering inward at Siren’s virtual world.

Cyborg senses and sensations like these are traced throughout Keogh’s book, ranging from subjects like the non-passive activity of seeing and hearing, how the experience of videogame time is constructed through rhythms of repetition, and the hybrid awareness of mobile videogame play striding the line between attention and inattention, among others. Though this is an academic text, which promises a rewarding experience for those who read intently, these chapters are written in an accessible language and remain grounded in tangible examples drawn from an eclectic variety of mainstream, big indie, and hobbyist videogames.

Readability aside, A Play of Bodies feels refreshingly contemporary as each chapter addresses ongoing discussions in videogame scholarship and criticism, such as the question of how videogames are cinematic, which Keogh approaches through an argument about synesthesia. Contrary to critical stances that would argue for an essential videogame-ness located in rules and systems, Keogh suggests videogames are essentially a hybrid media form and do not exist separate from their musical, filmic or ludic qualities.

Just as with film, speaking only about the story of a videogame without addressing how what the eye sees and the ear hears, without addressing how perspective and sound contribute to the telling of that story fails to describe much about videogames as a storytelling medium at all. It isn’t because of any long-take gimmick or photo-filter mode blessed by the estates of long-dead film directors that videogames should be considered cinematic, no. Rather, the simple fact that both mediums shape the experience of a spectator or player through the decidedly non-passive activity of seeing and hearing betrays their similarity, while validating the language we use to talk about film for use in the analysis and appreciation of videogames.

Keogh’s willingness to embrace an inclusive vocabulary like this enables him as he attempts to describe how an impression of time is created by videogames, drawing on a language of musical terminology. The stop and start repetition of player character death is framed in the book as a—if not the—major element of the rhythm of activity during videogame play. The focus remains on movements of cycles, which rings of the common descriptive phrase of ‘game loop’ to describe the repetitious, but meaningful sequences of activity structuring what we spend our time doing in videogames.

And to this end, Keogh is right to consider the influence of player character death upon this rhythm, though it proves to be a narrow focus at the expense of other elements of videogames that contribute to our felt impression of time. What his analysis has the adverse effect of revealing is, with few exceptions, and even less outside of videogames with perma-death mechanics, the death of a player character is a fairly insignificant event.

Rather, I think that the language of film would have served Keogh’s analysis of videogame time along similar lines but enabled him to go further. This is because, in a flat medium like film, an impression of space is conveyed through a language whose grammar is the duration of shots, the rapidity of edits, the continuity of cause and effect; poetically, time articulates space through metaphor. However, in another flat medium that accomplishes an impression of space so successfully, could the opposite be true for videogames: do we receive an impression of time through metaphors of space? Without consideration for the ways that long-distance travel and moments of dwelling effect an impression of time in videogames, the book leaves a lot left to consider about this topic.

I was inspired to ask, but left wondering, how should we imagine the shape of time in a videogame like Death Stranding when, after hours spent trekking across the world on foot obtaining access to vehicles allows me to traverse the same dreaded stretches of terrain with ease, speed, and pleasure? I can feel that time does not matter the same as it once did, and now the question becomes, how did it matter in the first place? But it is to Keogh’s credit that he does not claim to have issued the final word on this subject. Because of its incompleteness, A Play of Bodies remains an unconcluded project with room for further development by players, be they scholars, critics, or just enthusiasts.

One such direction in need of further development becomes apparent as Keogh traces the form of a normative cyborg body in an analysis of the co-evolution of controllers and the competency expected of players to succeed. Operating a controller is perhaps the most direct way we come to embody virtual sensations, yet the pleasures they afford are increasingly limited to a conventional wisdom dictated by what mainstream videogames and console manufacturers deign to be ideal: uninterrupted control in service of a technical proficiency.

The ideal player, Keogh concludes from his analysis, looks like a cyborg whose body is tuned to the rhythms, the audiovisual queues, and the embodied knowledge of decades of mainstream videogame design. This player is enabled to ‘play the game’ and succeed, while those cyborgs who lack proficiency to succeed, or seek videogame pleasures on different terms, are simply playing with the game in an inauthentic way, as it was probably said about whoever first turned on their co-operative teammates in the original version of Fortnite.

In all his work to outline the shape of a normative cyborg in the aesthetics of mainstream videogames and the phenomenology of the sensations available to it, Keogh forwards no descriptive language to suggest its opposite: the plurality of disabled bodies and queered styles of play. The omission of such bodies and experiences in a book about how bodies matter during the act of videogame play is, to be sure, a regrettable absence in this slight 199-page book. However, should their absence compel someone to describe how disabled bodies and queer playstyles matter in the act of videogame play, I believe that person would not find Keogh’s phenomenology to be exclusionary. Ultimately, it is a constructive and accessible way to begin describing how we see ourselves within the videogames that we play.

There is something telling about the way A Play of Bodies begins with and so often quotes the naïve and unconscious language of musician and hobbyist games scholar, David Sudnow, as he describes the felt sensation of playing videogames in his 1983 book Pilgrim in the Microworld. Before there was an academic discipline of game studies or an audience for games criticism, the feeling of playing Missile Command was “instantaneously punctuated picture music” and “supercerebral crystal clear Silicon Valley eye jazz.” By this I understand that articulating a phenomenology of the experience of videogame play is a project as old as videogames themselves. And because how it feels to play videogames is intrinsic to the experience of anyone who plays them, it’s a project that should be accessible to everyone. German compound words are not required for this task. Across bodies and across communities, there is a meaningful language we can create—if it does not already exist.

Comments

One response to “Trace Then Describe”

[…] Trace Then Describe – No Escape Braden Timss keeps the good book review times rolling at No Escape with a look at Brendan Keogh’s A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames. […]