I’ve worked the gig economy off and on for a few years now, but the one threshold I haven’t crossed for many reasons – and really can’t – is driving people from one place to another. (The main reason is simple: my car is a piece of shit inside and out.) As a result, I’ve been fascinated by games that take place in this world, with delivery drivers as the protagonists.

Drivers, especially drivers of people, are emotional laborers, and the work they do is much, much more than simply transporting bodies. Part of the way they make their money (and this is where the real separation between them and food deliverers like myself lies) is by essentially becoming five-minute friends with their passengers. What companies like Uber and Lyft tell their “not-employees” is that they should offer passengers water, let them sit in the front seat if they want, have a playlist prepared for everyone or even better, let the passenger choose the music, and by no means are they to bring their real-life problems into the job.

I can have a shit day at work, sign into the Uber Driver app and angrily deliver McDonalds to quarantined college students without talking to anyone for several hours and with minimal damage done to my tips or rating; an Uber passenger driver has to keep their customer service face on all day. But look, this isn’t anything new. Whether you call your job emotional labor or customer service, your life is in the hands of customers who do not care about you or your life but absolutely want to saddle you with theirs. There are a lot of customer service jobs that hold workers essentially hostage to customers, and this dynamic hasn’t shifted even a little bit in the middle of the pandemic. We’ve become more necessary in some ways but we’ve gained basically zero respect in the process.

So it’s interesting to me to see how video games treat this dynamic explicitly. In Cloudpunk, you play as an illicit delivery driver named Rania who gets roped into a city-shaking conspiracy; in Neo-Cab, you play as Lina, a gig-economy driver, who must find her friend and roommate before it’s too late (again, with city-shaking consequences); and in Night Call, you play as a taxi driver who was targeted by a serial killer, and is subsequently forced by a Parisian police officer to try to find your attempted murderer.

In each story, you are not the subject, but merely an object, a platform through which the plot progresses and other characters take the stage. As you ferry people or packages from place to place, everything but you divulges a part of the larger narrative. Even in a game like Neo-Cab, where the climax depends in large part on your relationship with your best friend, the way the game deals with this is by having you largely react to things your friend says to you. It’s only in Cloudpunk that the player is allowed to be an agent, a subject, because you can drive around. But even here, this ability to move freely can be taken from you by CorpSec or malignant AI that want you to answer their world-ending riddles.

I wish I could say with some amount of indignation in my voice that each of these games got it wrong, that they’re selling short the experience of being a delivery driver, a customer service person, an emotional laborer. But… no, actually, this is basically what every fucking day in customer service really does feel like, minus the minor adventure hallmarks of these games.

We’re subsumed into the stories of others, incidental and unimportant parts of so-called “Real Protagonists’” daily lives, and the rules of decorum we have to follow at any given moment are much stricter than theirs ever are. They can yell and scream in our faces or ears, willfully disregard our safety, trash our means of subsistence, and at best the companies we sell our labor to will apologize to them for a poor experience and not fire us. We can’t retaliate, raise our voices, express dissatisfaction in our treatment or rebuke them in any capacity. The best we can do is plead for them to “refrain from using that language with me so I can continue working with you.” Our professionalism has to be perfect while they can act however they feel like. If this feels more like a rant than a game analysis at this point, it’s because it is.

Helplessly careening through the night at the whims of strangers who do not care about you is not a flowery metaphor or allegory, it’s not a neat bit of storytelling. It’s not game designers going “hey let’s make our next game protagonist a character who was classically an NPC type in older games.” They’re drawing from experience in their own lives.

There’s a moment in Cloudpunk that horrifies me as much as it leaves me feeling sad. A major character is fading out of Rania’s life for good. We learn from them as they crackle out of existence that the only reason we knew them is because the debt corporations that exist in Nivalis as a truly terrifying force of reckoning (in a similar way to Kentucky Route Zero now that I think about it for like two seconds) literally fucking ripped their consciousness out of their dying body following an accident. “I was back at work before I even stopped screaming,” they tell Rania.

Night Call shows us Paris in the present day. Neo-Cab takes place in a not-exactly-distant neon future. Cloudpunk takes place in a time inconceivable to us. But each story is the same: the way things are is utterly fucked. People are stratified and kept in their place in society not by choice, indeed often by force, and with no other options. Those above dump their refuse and bad decisions on those below. Class solidarity is suppressed because everyone up to a certain point is “just trying to make ends meet” and the poisoned system is allowed to metastasize to a point of unsustainability. In the process our friends and family get hurt or killed and nobody bothers to notice. Even our very unimportance is leveraged against us by everyone from our real-world bosses threatening to fire us, knowing we need the job more badly than they need us, to the shady deuteragonists in the kinds of narratives games like Night Call and Cloudpunk employ.

I might just be sleeping badly, reeling from neverending Cyberpunk 2077 discourse and getting increasingly more upset at the paltry so-called “economic stimulus” the federal government is agreeing on tonight. But I’m tired of waiting for promised political saviors who come from the same economic class as the folks sitting on their hands with their thumbs in their ass, who either through negligence and lack of empathy or because they are willingly evil have left millions of us to suffer.

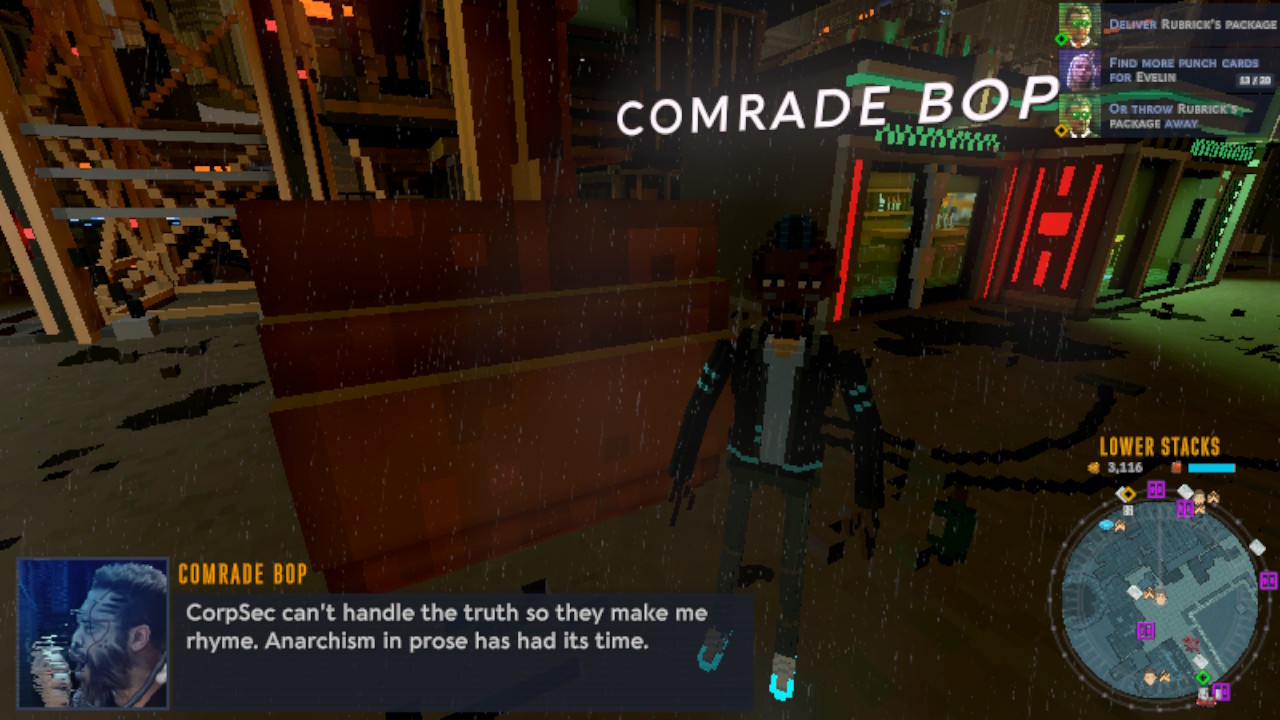

There’s a character I come across in Cloudpunk who I love. He’s an android named Comrade Bop. He’s an anarchist, and he has been forcibly reprogrammed to put everything he says into rhyme, otherwise he’ll explode. He’s bad at singing, and Rania gives him shit for it, but I can’t help but love him. He says at one point in our exchange, after Rania frets that he’ll be taken less seriously: “That’s their plan. But even if I have to sing every word, I’ll keep fighting the man.” Another group of characters, the gang BlockFourOh, goes around Nivalis and reclaims urban blight by turning the dilapidated city blocks into playgrounds and gardens. “There ain’t nothing in Nivalis that will get you in more trouble than fucking with corporate property,” they say. “We would be safer if we were straight murdering fools.”

These incidental characters crop up in the other games, as well. People who are frustrated with the present order of things, who choose to live apart from society or in opposition to it, radicals. A lot of folks would likely join them, if it wasn’t for the work they have to do to keep the lights on, feed their kids, stay housed. A lot of us, too, maybe wouldn’t just write about video games and/or work in call centers or drive Uber or work at the mall. But for the fact that we have never seen a bigger disparity between rich and poor in our lifetimes.

The federal minimum wage is seven dollars and 25 cents. There is no state in the country with rent so low that you could live by yourself on a full-time, bi-weekly paycheck where you’re making $7.25 an hour. Most customer service jobs start at a generous $11 an hour. You see where we have a problem.

What’s the solution, then? When will we all rise up? When will enough finally be enough?

I don’t know. It kind of feels like we passed that point a long time ago, but nobody realized yet.

And so, in the meantime, folks’ll keep making games about stories of late capitalism told in flying cars. And glimpses of a better world will shine through.

Comments

One response to “Late Capitalist Stories Are Told in Flying Cars”

[…] Late Capitalist Stories Are Told in Flying Cars – No Escape Kaile Hultner surmises that the craziest taxi game of all might be the fleeting friendships we form out of necessity under capitalism. […]