The angriest game I’ve ever played is one in which you never pick up a weapon. You never kill anyone. You don’t even hurt anyone. Mechanically a first-person shooter, this game takes the gun you’d normally find in a title about the end of the world and replaces it with a battered old SLR (Single-Lens Reflex) camera that you cobbled together from spare parts and trash.

You, by the way, are a courier for the Tauranga Express, a gig delivery service whose claim to fame is that it’s the fastest delivery service in Tauranga, Aotearoa. You have ten minutes or less to deliver your parcels to your clients, and meanwhile you have a checklist of interesting things to photograph to make a little extra money on the side. Also, the world is ending due to a mixture of government incompetence and forces of nature far beyond human understanding. This is the life and times of the Umurangi (te reo Māori: Red Sky) Generation, by Māori developer Veselekov.

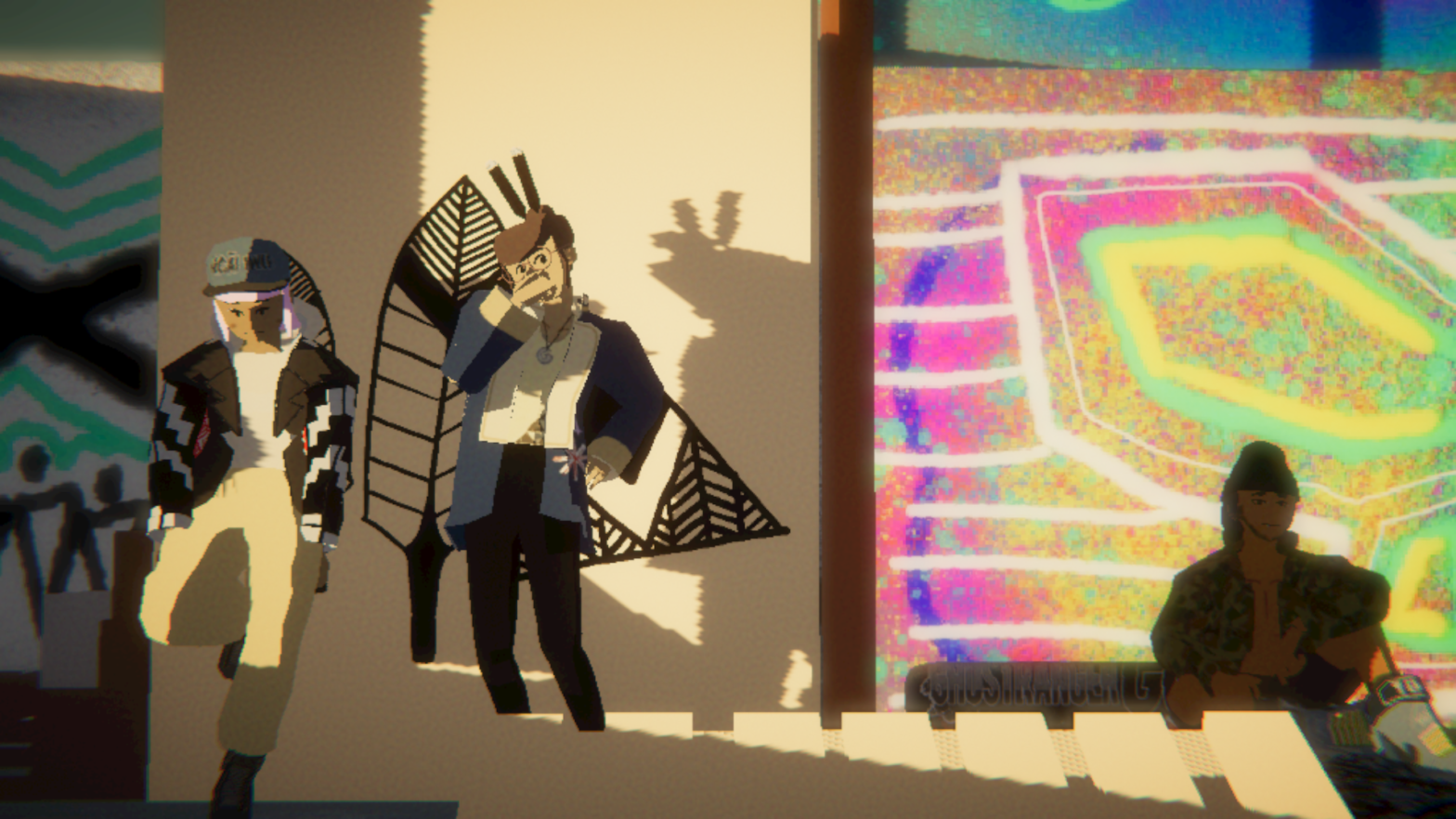

I recognize that calling this “the angriest game I’ve ever played” might give you the wrong idea. When you start the game on a rooftop in Mauau View, the general atmosphere is as chill as you could possibly get. You and your friends have set up an extremely relaxed rooftop hideout/getaway, complete with a pool, a penguin, a half-pipe and all the graffiti tools you could ever find yourself needing. Down at street level, the only hint that something might be wrong is the presence of looming barricades erected by the United Nations peacekeeping force that has holed up in your city. God is in his heaven, though, and all’s still right in the world. For now.

As you progress through the game, you are able to upgrade your photographic arsenal, as it were. When you complete bonus objectives, like collect a certain number of film rolls, even more equipment becomes available to you, like new color and exposure sliders that allow for a finer-tuned post-processing, and items like flashes. This game basically begs to be played over and over, and each level is its own discrete snapshot, as it were, allowing you to return to areas you’ve already been to easily.

Completing your main objectives only loom over you on your first run. I admittedly found some of the objectives in some of the missions quite challenging, but the game heavily encourages exploration and doesn’t overly penalize you for missing your delivery window. The objectives never change, so the next time you play a particular zone you can collect them all with a quickness and then explore to your heart’s content. And with so much loving detail put into each area, you will want to explore.

Once you’re out of the relative comfort of Mauau View, hints at a darker, sadder world start to become more apparent. In one moment, you’re on a different rooftop with a squad of UN peacekeepers your friends know. They have a mortar they’ve named “Sharkie” and there’s a dedicated “vape zone” in the encampment. They’re from the neighborhood, or at least, from your neck of the Pacific, and they are not pleased to be on this rooftop while it’s raining.

In another part of Tauranga, a “UN No-Go Zone,” phosphorescent murals tower above you on the sides of high-rise buildings, intricate butterflies and wolves and other animals, as well as people, competing for your visual attention with the abundance of neon signage that can be found in these parts. Memorials have been set up for people in the neighborhood who have been “lost” to whatever is going on. Everywhere people are loitering, contemplating, mourning. The overwhelming sense is there’s nothing better to do. Anger at the UN and the cops is palpable.

A photographer’s job during times of crisis is to observe and document everything around them, as respectfully and as honestly as they can. Photographers sometimes have kind of a really bad track record at doing the latter bit. There is a risk I feel in a game like this – not that there’s really any other games like this, to be honest – of falling into the role of a tourist. I’m observing, sure, but because I’m not part of this moment, because I’m not from here, the gravitas may be lost on me.

I don’t think this is true for the character, though. She is largely unnoticed, or if she is noticed, she’s recognized as a local. Nobody ever objects to having a lens stuck in their face and their picture taken, even in the game’s hardest moments (which might be the only truly unrealistic aspect of the photography, to be honest).

It is harrowing to consider that the last generation may have been born already, that a group of kids who should absolutely have a fucking future may already be growing up in a world in which they assuredly don’t. Umurangi Generation forces you to consider exactly that. Underneath the aesthetic trappings and the… familiar narrative dressing, the game puts you in a world that is already dead, and yet the systems and mores and cultural glue that we think of as society are still there, still running, however poorly. You inch closer to the precipice, but meanwhile food still costs money and you have a perfectly good, if makeshift, camera with which to take photos and sell them for bounties.

In 2019, a fire swept across Australia, turning the skies blood red. It took over a month to put out, countless lives were lost, and the government basically sat back and did nothing. The prime minister even went on a vacation during the crisis. It was the worst natural disaster caused by climate change, and worse yet, no one who was ostensibly in charge seemed to care all that much apart from lamenting how much private property was destroyed. Similar fires have engulfed Brazil and to a lesser extent the US west coast, all within the past year. The climate is changing, and climate scientists have emphatically made it clear that we have maybe a decade to halt our current trajectory.

We’re all currently stuck inside because of a virus. The people continuing to leave their houses either have to because the machinery of capitalism refused to slow down enough to not run them over, or they’re repugnant jackasses who think they’re super-libertarians because they confused lizard-brained contrarianism with some bullshit called the “non-aggression principle.” In my state, the sheriff is making plans to evict hundreds of people within the next week. During a health emergency. It’s hard to organize at the moment and even harder to create any alternative types of resistance, because fuck, the only shitbirds protesting outside right now are the armed militias holding Michigan’s state legislature hostage. People are being attacked because they’re wearing masks. People are also being attacked because they asked their attackers to put masks on too. People are being attacked because fuck you, this McDonalds lobby should be OPEN god dammit.

And we’re supposed to stop… climate change next?

Against this backdrop that evokes nothing but fresh despair, you might wonder if playing Umurangi Generation is a mistake. It is literally dedicated to the last generation to watch the world die. You expect this thing dripping with nihilistic apathy, but if that is what you take from this game? Come on now. Instead, everything is so fucking vibrant. The music by Thor HighHeels/Adolf Nomura is so rich and perfect. The world might be dying or dead – husks of twisted steel against a blood red sky – but everyone and everything that remains – the streets you walk at night, your friends, the groups of dancing street punks and ravers with their neon Mohawks, the birds and cats and every glittering sign advertising Gamer’s Paradise in the darkness – lives beautifully in spite of everything.

And you’re there to chronicle it all, a simple courier for the Tauranga Express with a beat-up camera.

In the game’s final moments, you have no delivery requirements. The 10-minute time limit is gone. You simply walk up the path, camera in hand, and take one final shot. Your friends are all there, outlined in starlight. The end of the world came but you all lived lives of beauty and wonder and danger, and now it’s time to go on ahead.

I called this game one of the angriest I’ve ever played. I want to make sure, at the end of this, that you understand. It’s not angry at any particular character you interact with. One of your bonus objectives on each stage is to get a group shot of all your buddies, including a very cool penguin friend. Sure, there are anti-cop and anti-UN slogans everywhere, as you’d expect in situation where a country becomes twice occupied – first by colonizers, then by peacekeepers. In one area, however, you see murals of a local woman – dressed in mismatched UN peacekeeper gear – who led the fight in the neighborhood against the game’s largely unseen monsters. She’s celebrated and mourned. “Here is where on 2/8/97 Maxine from Lot 27 rose to protect us from [redacted] invaders. Kia kaha moana.”

The game is advertised as a photography game set in the “shitty future.” The anger is reserved for those who are currently directing us toward that shitty future, and to those who believe it is inevitable, not out of despair, but because they want it to happen.

What I would like to see happen, as we wrap up this monster of a review, is for you to go read pieces on this incredible game by Māori writers and watch playthroughs of the game by Māori streamers. One great resource for that is to simply follow Umurangi Generation‘s Twitter account. There you’ll find links and retweets to a bunch of creators’ videos, streams and photo galleries. It’s good as shit, folks, and they’ve got some perspectives on this game that you’d be missing if all you read was this piece.

It’s a genuine pleasure to have you here reading our work. If you enjoy it, follow us on Twitter. If you’d like to read a bunch of work like this, you can check out this book-esque object over at itch.io and, soon, other platforms as well!