About a month ago I stopped subscribing to the Verso Book Club. But before I turned my back on book clubs and the waterfall of texts they were sending me, I made one last purchase: Taking a Long Look: Essays on Culture, Literature, and Feminism in Our Time, by critic Vivian Gornick. I wanted a companion to Ursula K. Le Guin’s Words Are My Matter, I think; plus it’s never bad to read criticism outside of your wheelhouse (especially if your wheelhouse is video games). I got it a couple weeks ago, and cracked it open just a few days ago. I immediately, unexpectedly, got bodied by the first sentence of the book’s introduction.

“I can remember the exact moment when I left polemical journalism behind me to begin the kind of nonfiction storytelling I had longed, since childhood, to write,” she writes.

It felt like the truck hit me straight in the solar plexus at 90 miles-per-hour. I had a little bit of trouble breathing. Tears welled in my eyes. I had to put the book down. The pain and pressure of realization washed over me, a full-body shiver that took about 90 seconds to spread from my head to my toes. I couldn’t rationalize it, and I still can’t: this is a pretty anodyne sentence to start a book of essays out with. But for the first time I felt like I had a clear sense of myself as a writer.

The moment passed and I read on, learning about how Gornick navigated her career from precocious young writer to Village Voice journalist to the memoir writing and cultural criticism she’s principally known for today. It’s all very interesting, absolutely would recommend. But that moment, though.

That sliver of fucked time, a lightning-strike of self-consciousness more keen than my anxiety-ridden ass usually feels. I can remember the exact moment when-

Another book I’ve been reading lately, Hannah Nicklin’s Writing Games: Theory and Practice, is an incredible no-bullshit primer on the meat-and-potatoes of video game writing. There are extensive vocabulary sections and discussions of different film and literary theory and a whole second half of the book I haven’t gotten to yet that just features practice activities. It is exactly the kind of book I’ve low-key been searching for for years, and even though I’m not out of the theory/vocabulary section yet, I already feel like I’m more knowledgeable about how the stories of games get written now than I was even just a few weeks ago. It almost has me raring to write a game scenario.

Except

People in game critic circles already know Gareth Damian Martin. They are the editor-in-chief of the unrivaled Heterotopias zine, one of the best critical spaces on game architecture and aesthetics, hands-down. They are also the developer, as Jump Over The Age, of the excellent 2020 text adventure In Other Waters. Recently their second game, Citizen Sleeper, came out on Xbox Game Pass and the Nintendo Switch eShop to well-deserved rave reviews. And folks, believe the hype: the game slaps.

Citizen Sleeper is an RPG set in a zombified-late-capitalist far future where humanity has expanded to the far reaches of the galaxy. Interstellar travel as well as planetary terraforming and colonization are all not only possible but routinely done, and as a result, the species has proliferated in wild and wonderful ways. But this is a zombified-late-capitalist far future, not a utopian-luxury-space-communist one; corporations are still corporations, and capitalist hegemony still has its iron grip on us all. This might be disheartening (and maybe a little bit perplexing) to the anti-capitalism-inclined, but it sets up a great central conflict for the game itself.

We play as the titular Sleeper, a being one might think of at first as a kind of android, but it’s a little bit more complicated than that. I’d compare them to the Exos in the Destiny franchise, a cohort of human consciousnesses bootstrapped into corporate-owned mechanical humanoid frames. Sleepers are forked digital emulations of flesh-and-blood people who sign their bodies and minds over to the Essen Arp Corporation in order to find gainful employment.

The mechanical frames these consciousnesses are inserted into are highly durable and eminently capable, but all are built with a fatal flaw: “Planned Obsolescence,” the accelerated decay of their systems and functions that occurs if they don’t get a proprietary cocktail of supplements from the corporation each day. Planned Obsolescence in this case doesn’t kill you instantly if you run the clock out on it, but the longer the degeneration is allowed to progress, the less durable and capable the mechanical body becomes. This accelerated decay paired with the dependence on proprietary drugs to keep going is meant to keep Sleepers from escaping. After all: you wouldn’t download a body, would you?

Wait – why would Sleepers think of escaping? Hahahahaha, well, uh 👀

We are a Sleeper who has barely escaped with their life after boarding a freighter and landing on Erlin’s Eye, a “lawless” space station at the far reaches of the galaxy. We turn out to unfortunately be the lucky one; our comrades in escape didn’t make it. And so, alone, hunted, with no access to money or contacts or other resources to keep ourselves going, we have to scrape together an existence on this station, any way that we can.

I say “alone,” but honestly that’s never fully true. From the get-go, we are assisted by a motley assortment of characters, from the scrapyard foreman who finds us and asks us for shipbreaking help to the fungus cook who feeds us for free on our first full “cycle.” And as we get further divorced from our dire straits, we find more and more people willing to help – with varying degrees of ulterior motive, of course. Every supporting character is exquisitely well-written, and through Martin’s prose and the intuitive gameplay we get a wonderful sense of place out of the station itself, on both a macro and a micro level.

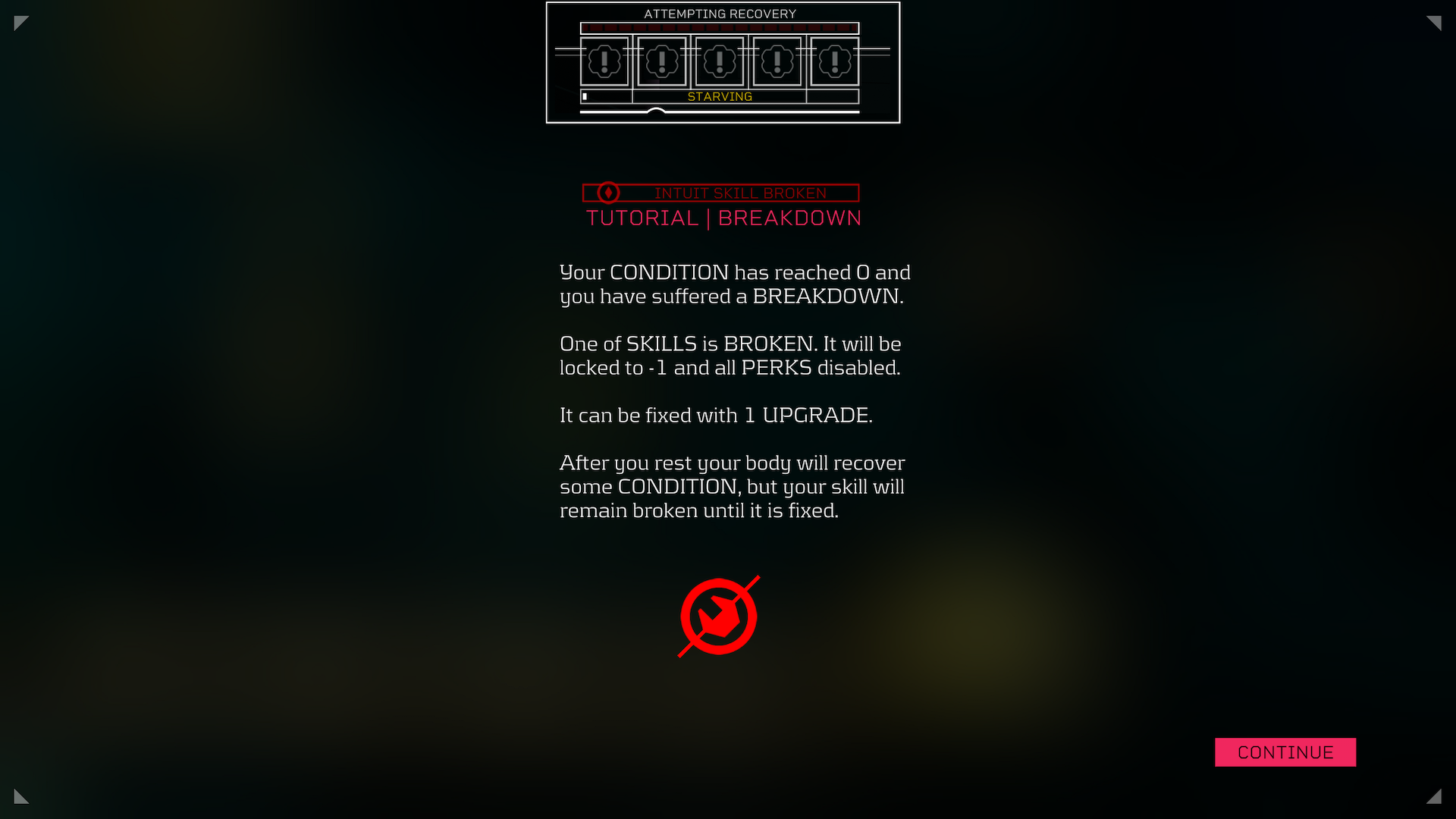

Ah – but let’s talk about that gameplay some more. TTRPG fans will love this game, as its mechanics are liberally inspired by games like Blades in the Dark, Lancer and Fate, as well as a number of solo TTRPGs out there. The core conceit is simple: Every day, or cycle, you start with a randomly-rolled set of dice that represent the total number of actions you can take that day, with the maximum number of actions capping out at five. As you expend energy and your body degrades, the number of dice you start each cycle with decreases. Eventually, if you starve and don’t find a way to beat back the Planned Obsolescence, you get one single dice to use. Because the dice are randomly-rolled, some actions might be natural successes, while others might be neutral or even negative. Our goal as the Sleeper is to use our limited actions to essentially cheese our way out of destitution.

The game is also a race against time in a different way. As we meet people and agree to help them with various tasks in return for help with our own problems, we might find that the time for us to complete their task is limited to just a few cycles, and a clock will pop up to remind us of this fact. Additionally, some characters will simply disappear for a while, and clocks appear to let us know when they are expected to return. As we complete tasks for people, we cross off “drives” and earn skill points that can increase our “luck” with certain dice rolls and enhance perks that award us with materials, stamina or other resources for participating in our daily grind.

With art by Guillaume Singelin and music and sound design by Amos Roddy, Citizen Sleeper is a genuinely gorgeous and rich game that gently reminds you that staying still is not always the best option, even if you manage to pull yourself – or get pulled – into a better place. It also gently compels you to think about those moments in your life where sacrifices or compromises had to be made, and how the “choice” to make them wasn’t always voluntary, nor was it always yours to make in the first place.

I can remember the exact moment when I left my dream of storytelling behind me.

Martin’s ludic body of work deals heavily in themes of self-determination, and breaking expectations and conventions of expression and experience. It can sometimes also veer into the slightly discomfiting, as I found out toward the end of my Citizen Sleeper run.

As a Machinist (one of the three classes to choose from, alongside Operator and Extractor), I benefitted throughout the game from a perk that randomly awarded me scrap materials for doing engineering tasks. Because I didn’t really have a need for it, this scrap just kind of built up over time; sometimes an NPC would ask for some, or I’d go to one of the shops to exchange it for Chits, the game’s “cryptocurrency” (don’t worry, this game does not have actual blockchain technology in it).

But as I checked off more and more drives and earned more and more skill points, I was able to get into a position where I was able to afford the “Self-Repair” perk. This perk allowed me to, if I wanted, maintain my frame’s condition without needing to use the supplements anymore. This coincided with a moment where my primary source of the supplement just outright gave me what they had left, and suddenly I found myself no longer in a precarious position. I had a home where I could feed the stray alley cat crackers. I had a mess of Chits and nothing to spend them on. I could harvest scrap just about indefinitely and therefore repair my body forever, without ever even dipping into my generous supply of drugs.

Relative to several characters on the Eye, I was suddenly doing extremely well for myself – maybe I wasn’t running Yatagan or in the upper echelons of Haveneye, but I also no longer had to scramble and scrap for enough Chits to buy a meal, or agonize over whether I should try and go for a shipmind fragment to move a clock along or buy another pill to sustain myself for another handful of cycles. And it made me feel kind of weird!

It wasn’t a feeling I was unfamiliar with, though. It more or less reflected the position I’m in now, in my real life. And that felt weirdest of all.

I wanted to be a writer when I was a kid. And I don’t mean a journalist or a critic; I wanted to write fiction. I especially loved stories that veered into the weird or macabre. Stephen King became my favorite author, though I also fucked around with the work of Peter Straub, Dean Koontz and a few others in that space. I don’t know how others felt about my interests for the first few years I practiced at it, but as I got closer and closer to high school, the more I felt like “becoming a horror writer” was what I wanted to do with my life. When I entered freshman year of high school, I can’t say I started off on the right foot, coming into conflict with my first English teacher almost immediately. I got switched to another teacher the next semester, but a few things coalesced at once to change my life significantly in the interim.

The first thing to happen was something completely divorced from my circumstances but which set the national tone: the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007. There were a lot of genuinely terrible and disturbing factors involved in that incident that galvanized the national imagination; one of them happened to be that the shooter liked to write horror stories.

The second thing to happen was that, in the process of trying to move into another English class, I came into conflict with my school’s freshman principal, who didn’t understand why I shouldn’t just stay where I was. The more we butted heads on that, the less he liked me (and where we started was already pretty low). Eventually the transfer happened, and the teacher I ended up with was genuinely delightful. We had a great time reading Shakespeare and Sophocles and watching the Baz Luhrmann-directed Romeo + Juliet, as well as Hitchcock’s Rear Window for some reason? It was fantastic.

The third thing to happen was a rumored shakeup in the school’s administration; we were getting a new principal, and the current hierarchy was going to be shifting. I can’t really speak to this aspect so well, because I really didn’t pay attention to this; but it stands to reason that administrators were probably busy jockeying for favor with the new head of the school.

One day, well after the transfer and right before summer vacation, I was called into the freshman principal’s office, a small, closet-sized room in an annex adjacent to the main admin offices. The room’s walls were bare apart from a school-themed calendar and the building’s emergency evacuation plan. On the man’s desk were pictures of the freshman football team, a stuffed husky (the school’s mascot), his workstation, and a closed manila envelope.

He beckoned for me to shut the door behind me on entry, and to sit down in one of the small, uncomfortable chairs across from him. After some strained small-talk, he cut to the chase. He asked me if I had seen or heard of the Virginia Tech shooting the previous month; I indicated I had. He then proceeded to tell me that “several people” had informed him that I was exhibiting “alarming behavior,” and he intended to take action to make sure his students were safe. He told me that he had been informed of my interest in horror fiction, and that he was concerned that, if allowed to continue just doing my thing, that I would “escalate.”

I sat there in stunned silence. He told me my locker would be searched the next day and if any “evidence” as to a “plot” was found, it would result in possible disciplinary action. The implication was clear. He asked me if I had anything to say for myself. Holding back tears as valiantly as I could, I tried to put up a defense. I said I loved my friends; I loved art class and photography and I loved coming to school; that I would never do anything to hurt anyone. All he said in response was, “we’ll see.”

My parents freaked out. They were livid at the school, but saved a little of that ire for me. They told me to throw out my writing so that nobody could “accuse me of being a shooter anymore.” They told me to throw out my collection of Stephen King books. They told me to keep my shit together for the rest of the year “so that those assholes don’t have any excuses.” That was the end of my dream of becoming a storyteller.

I kept up writing, of course. I got active in Yearbook the next year, then switched over to the journalism class and the school newspaper. I learned from my journalism teacher all the basic rules of the trade: how to interview, how to copy-edit, how to come up with succinct prose to describe events that happened in front of me. I decided I would still become a writer, but instead of titillating audiences with spooks and scares, I would speak truth to power and uncover corruption. It was around this time that I fell face-first into anarchism; you can imagine how effortlessly these Big Ideas coalesced with my newfound calling.

I can’t write fiction to this day, however. There’s a block in my brain I’ve been trying to dislodge. I feel the urge to create, but I can’t get past a few sentences. Reading works like Nicklin’s Writing for Games and Le Guin’s fictional and critical oeuvre, doing close reads on games for a few years – these things have helped, but nothing has actually managed to get the block out completely yet. And then there’s the other shoe: I work a day job, a crummy 10-7 where a good chunk of my creative energies are wasted on corporate bullshit. When I get off, I don’t have many dice left to spend on pursuits I actually want to spend them on. But I am able to survive, such as it is. And of course there’s still time for me to figure shit out: Gornick was in her 50s when her first memoir was published, and she put out Taking a Long Look in 2021, in her 80s.

Escape is still possible, if I want it.

One thought on “You Wouldn’t Download a Body”

Comments are closed.