In “Who Has To Do It?” anarchist writer Lee Shevek asks her audience an important question: what if, in the most ideal anarchist society you can think of – all modes of domination and oppression eliminated – a task arises that absolutely nobody wants to do voluntarily? Would we force someone to do the task anyway? Or would we find a way to remodel society around the conditions that make the task necessary?

For Shevek, the question is nearly rhetorical, but still worth posing; her clear answer is, “If no one willingly goes down into the mines, we will create ways of being that don’t require the resources there.” For Cain, an anarchist game developer living in Narrm (so-called Melbourne), the question and its ramifications are more… muddy. His attempt at answering it, short interactive fiction piece Waste Eater, posits a world in which both things have happened: humanity has evolved to survive around the apocalypse, and some people had to be sacrificed to the effort to make the world less uninhabitable. What follows is an exceptionally powerful vignette in the life of the last Waste Eater as, no longer able to survive without a source of toxic waste, they wait to die.

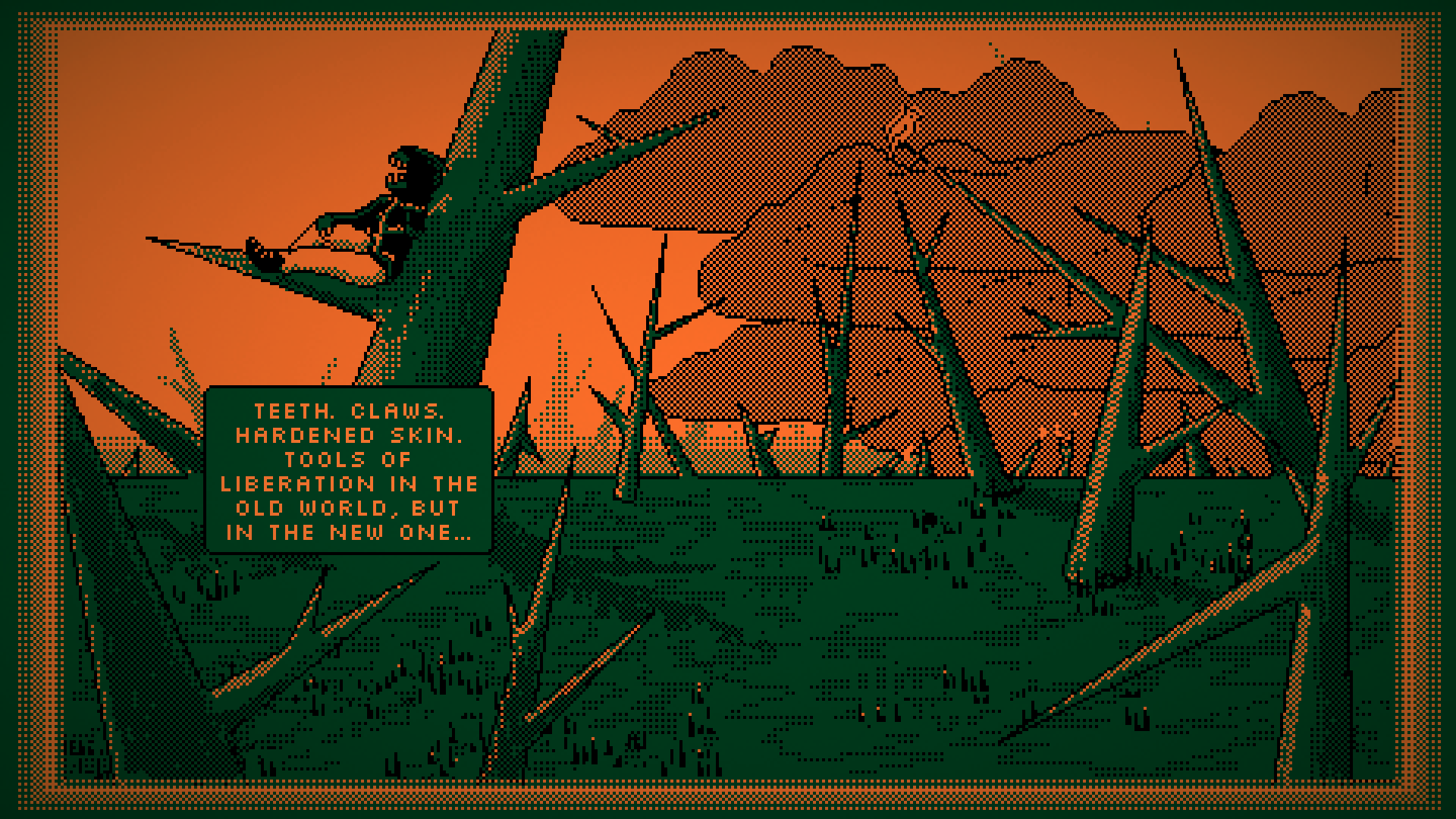

Aesthetically, players will immediately recognize the landscape – lovingly rendered in a 2-bit orange and green pixel style – as calling back to the infamous thorns landscape conceived by Sandia National Laboratories’ Michael Brill and artist Safdar Abidi in 1993. These thorns were, according to the WIPP proposal, “Shapes that hurt the body and shapes that communicate danger.” It’s fitting that the Waste Eater is sitting perched on top of one of these thorns, a sign of their ability to exist in a space we couldn’t, that what harms us barely phases the Waste Eater and their kin.

We meet them right as they’ve emptied their last stores of waste. Their reserves are critically low, and they barely have the energy to move. Their companion: a bird, a rare sight in the wastelands, though perceptive players will note the thin-yet-persistent scrim of grass growing at the thorns’ base. Life is slowly returning here, a result of the Waste Eater’s lifetime work.

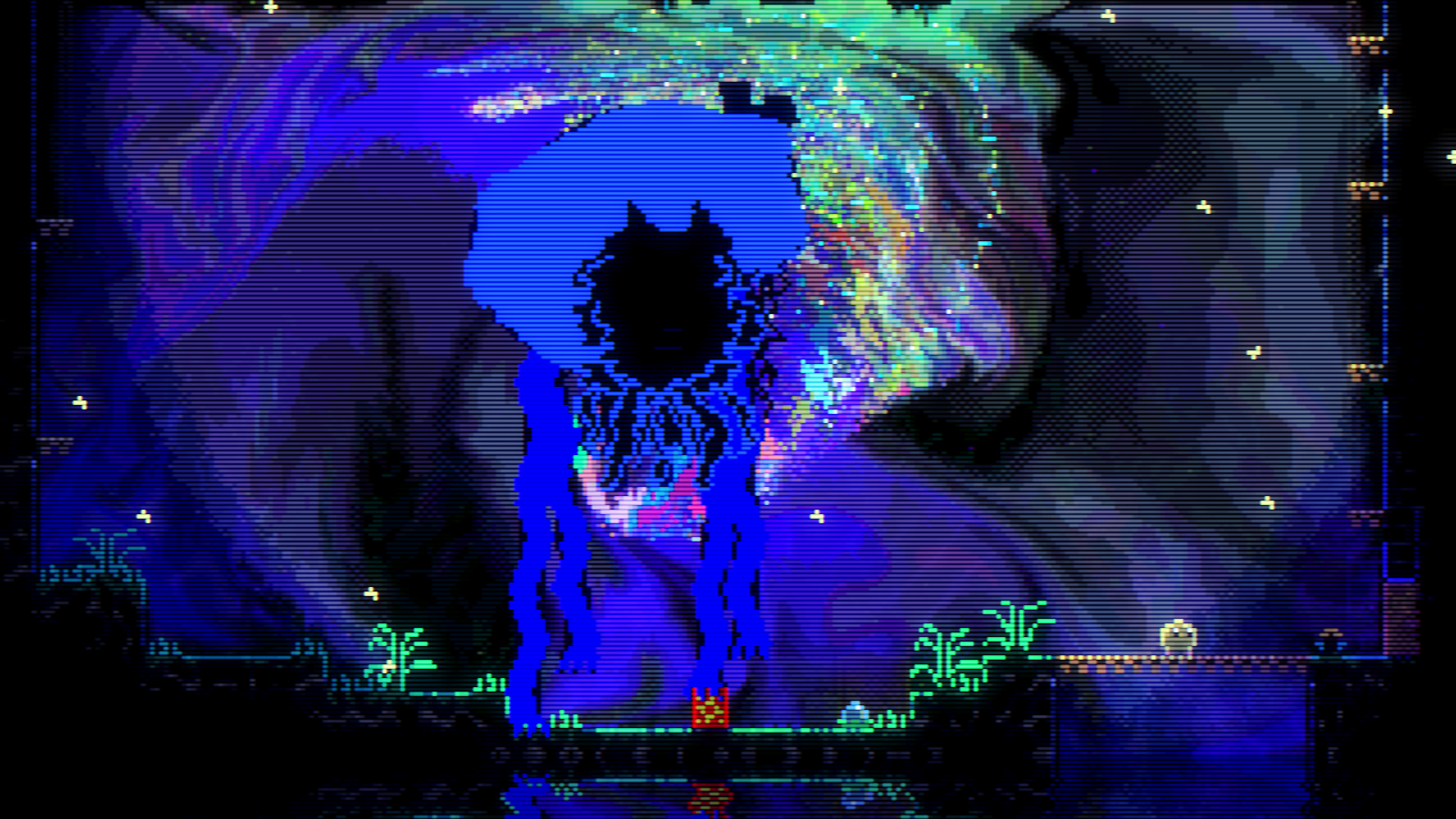

The Waste Eater tells us stories from their life, memories of the other people who entered and exited it, and how they feel about being separate from the society they’ve helped bring back from the brink of destruction. They talk about their regrets, their wishes for the future, and even hint at the procedure that made them a Waste Eater in the first place. All the while, their waste reserves drop lower and lower. Finally, a dust storm rolls in, and they commit to their final moment not in peace, but with resignation.

Simultaneously a meditation on our own climate future, the deleterious labor we do to maintain society as it is, and a vision of hopefully better things to come, Waste Eater was a surprising experience. Play until the end. It hits hard.

One response

[…] Year of Games #3: Waste Eater | No Escape Kaile Hultner plays a game about sustainability and sacrifice. […]