It’s been a while so let’s do the rundown: this post is going to have major spoilers for UN Hangar, the second level in Umurangi Generation Macro. If you would rather not read spoilers of Umurangi Generation Macro, feel free to skip. If you would rather read and complain about my inclusion of spoilers, I’ll fight you in whatever parking lot is most convenient.

Here are the previous posts in this series: Part One. Part Two. Part Three. Part Four.

Before we begin I just want to make kind of a funny note: I’ve been playing with Umurangi Generation for so long now that I can say I’ve played it on just about every platform type it’s come out on, starting with the demo and original game on PC, moving to Switch, and finally landing on Xbox Game Pass. That’s two years and a lot of ways to play this game.

Anyway.

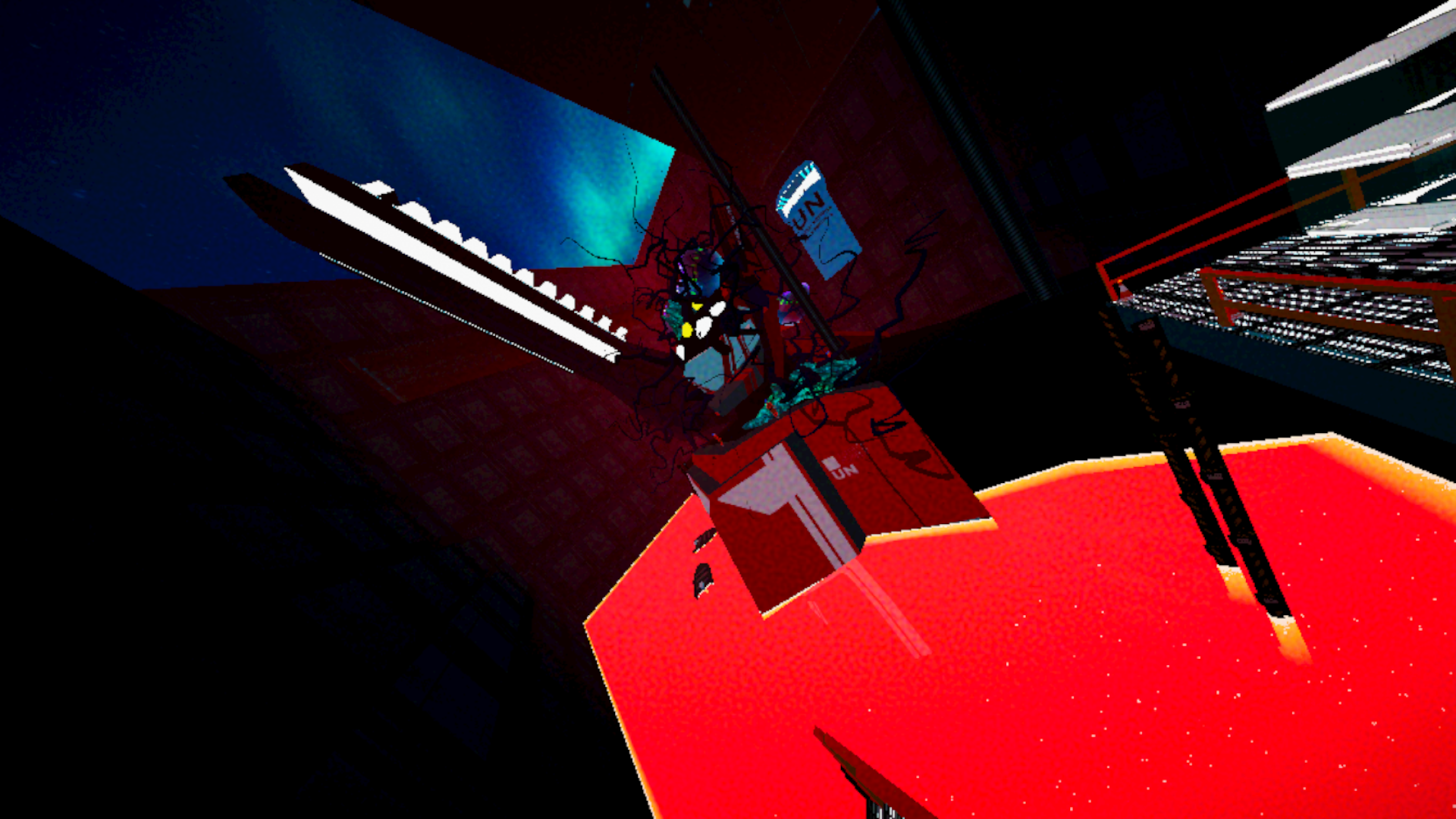

UN Hangar is hard to talk about from the perspective of trying to play hide and seek with the game’s diegesis. We’re in a UN hangar. There’s a giant mech in the hangar. All of its different accessories and such are scattered around the outer periphery of the hangar. We get to explore the hangar with almost no limitations. That’s about it. There are still Narrative Things Happening here, but the centerpiece is the Peace Sentinel, that giant fuckoff mech in the middle of the room.

I love me a good mech. Mechs are cool. The stories they often appear in are frequently very complicated, both from a story and an ethical perspective. We could probably talk for days about Armored Core or Daemon x Machina or Front Mission or Into the Breach or Zone of the Enders or MechWarrior or Gundam or Evangelion or Eureka Seven or Aldnoah.Zero or Code Geass or Escaflowne. We could go over in great detail why it is that kids are often the ones piloting these robots. We could spend more time than is currently available to living human beings debating the religious and sociopolitical and technological questions mecha as a genre brings to the fore. But ironically, doing so in this context would be falling into the “Wow, Cool Robot!” trap.

The Peace Sentinel in the hangar is the centerpiece for the same reason that a Tier 1 Operator is the centerpiece of a covert-ops-centered first-person shooter; for the same reason that an F-35 is the fastest currently-existing fighter jet in Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown; for the same reason that Guardians are the literal fulcrum of the universe in Destiny. UN Hangar, as a level, as part of Tali Faulkner’s project on exploring the fascist environment that led to the in-game world’s destruction, is where we come to understand how the bulk of the UN’s fascist power is expressed and enforced. The Peace Sentinel is the center of power and agency in this world. As such, it is the place to talk about “interpellation” and “hegemonic pleasures.”

Let’s imagine for a second that Umurangi Generation was not an anti-colonial anti-capitalist polemic against the “West’s” response to global climate change, and was instead the opposite: a piece of patriotic propaganda disguised as a Cool Dreamcastlike Mech Shooter where players could step into the role of a British or American United Nations Peace Sentinel Pilot and fend off the Kaiju threatening New Zealand and the world. Some of the missions require you to pilot the Peace Sentinel to suppress the people who live in the area you’re protecting, but it’s for their own good: we have to keep them in line to keep them safe while the bigger threat of the Kaiju looms over us. One mission in particular ends with us summarily executing an entire anti-UN terrorist cell. It’s for their own good. “You’re either with us or you’re with the Kaiju.”

Would players blink at that? Would you? This is the intended result of interpellation, the process by which an institution (or in this case a cultural object, like a game) draws you into itself such that you have no choice but to not only support but actively take part in its ideology while engaged. To be clear, every game does this; Umurangi Generation as it actually exists does this as well, but back towards the “anti-colonial anti-capitalist” perspective. But that’s not all that is happening here. In addition to that interpellation effect, players are also contending with what are known as “hegemonic pleasures,” which media scholar John Fiske defined as “The pleasures of conformity by which power and its disciplinary thrust are internalized… and… widely experienced.”[1]Fiske, John. Understanding Popular Culture. 2nd ed, Routledge, 2011. By accepting the game’s logics, by getting into the robot, players would willingly perform tasks they might otherwise find unacceptable because it’s still empowering.

And that is why the Peace Sentinel takes up so much space in the hangar. It is meant to be seen as a locus of fascist power and hegemonic control. And it’s also why it’s so important for players to grab the keycard for another hangar off the lunching worker. In this other hangar is another mech, but this mech is damaged, corrupted, covered in giant Blue Bottle jellyfish. This hangar is much more empty, much less triumphant, almost funereal – a sign that the power these fascists hold is both conditional and not particularly substantive.

Nevertheless, the UN still negatively impacts the region, as we will see in The Depths.

References

| ↑1 | Fiske, John. Understanding Popular Culture. 2nd ed, Routledge, 2011. |

|---|