Seasonal Book Club is a new recurring feature here at No Escape, wherein I try to get through a book about video games, one chapter at a time. This season’s book club entry is The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games: Why Gaming Culture is the Worst, by Christopher A. Paul.

So I wanted to start off this first issue of Book Club with a little sample of some of the best negative Amazon reviews of this book and its author, Chris A. Paul, Associated Professor of Communication at Seattle University.

Let me get this straight. Gaming rewards success…and that’s a bad thing? Attacking meritocracy is promoting nepotism. It’s saying, “I deserve a promotion for failing because I’m friends with the guy who runs things.” This is a giant delusional ramble by a guy who thinks empiricism is naive; that is to say, truth is too offensive to be considered true so we should just put our fingers in our ears and cry when truth is seen.

— Big Chungus, Amazon Reviewer

Competition is problematic because I always lose. However, I DO have a communication degree, which makes me well qualified to rationalize my under-achievement and blame others for my failures. I envision a utopia in which everyone who is good at anything is handicapped, and all outcomes managed or randomized, to ensure that EVERYONE feels included.

— The Golden One, Amazon Reviewer

Filled with rambling nonsense. I’m not even sure how to write a proper review for it. Save yourself a headache and avoid.

— Sargon of Akkad, Amazon Reviewer

Quite possibly one of the worst books to be vomited out by an academic in the past 30 years. Ghastly, overpriced, turgid and with a premise divorced from reality, predicated on a promoting a concept that has universally failed while condemning that which has been the founding premise of the most successful societies in modern history. Extra star given because the prose is slightly better than what most academics produce these days. That, however, is just window dressing on utter nonsense.

— The Quartering, Amazon Reviewer

Enough gamers told this author to “gid gud”, and he cried a book out of it, impressive.

— Duke Amiel d’Hardcore, Amazon Reviewer

*All names have been changed.

On the other side of this coin, over at First Person Scholar, David Schwartz wrestles with the notion of having to review a book that explicitly calls out the kind of culture reviewing contributes to:

Identifying meritocracy as a system in which skill is measured and outcomes tracked, with a mixture of talent and hard work rewarded, the author states that “meritocracy isolates, individualizes, and strips out context” (13). And what is a book review, if not precisely that process? The reviewer is tasked with dissecting a work which is usually the product of years of labor, charting its strengths and, if catty, reveling in its weaknesses. It is difficult to imagine how to review a book, if not under some form of meritocratic system.

My difficulties with conceptualizing a non-meritocratic review, perhaps, illustrate just how hard-wired meritocratic norms are—especially in academia—which demonstrates that this book makes a very good point about thinking more closely about the meritocratic structure of video games.[1]Book Review: The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games – First Person Scholar. 26 Sept. 2018, http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/book-review-toxic-meritocracy/.

I wanted to tackle The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games first in this book club for a few reasons. The title is wild; the inside contents are sound and well-researched; and it shares its central premise with No Escape and what we want to do here. It helps immensely that Paul organizes his chapters to stand on their own even as they support his overall thesis.

This part covers the introduction and chapter one. Future parts will cover only single chapters. All (Parenthetical) citations are page numbers. Anything else will be linked to.

What is a meritocracy? How does it pertain to video games? Why, contrary to the belief of at least a few upset Amazon reviewers, is meritocracy bad? And where can we improve material conditions in the places it has touched? From page one, Chris Paul sets out to answer these important questions. He describes his young life in relation to playing games, reminiscing that video games faced very different problems when he was a kid: “I have often had to defend video games from concerns about what they would do to me or worries about how I could be better spending my time. […] I understand that there was a time when video games were marginalized, relegated to arcades you weren’t supposed to go to, and subject to concerns about your brain rotting, how much time you were wasting, or the violence they might inspire in the susceptible. However, while these complaints can still be seen on occasion, we are no longer in the same kind of cultural moment.” (Paul[2]Paul, Christopher A. The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games: Why Gaming Culture Is the Worst. University of Minnesota Press, 2018. 1-2)

The cultural moment we are currently in is one where “limited depictions of women and people of color” and reactionary movements like GamerGate are the norm. “The current state of culture around video games is dark, and I think those of us who recognize problems have an obligation to address them,” he writes (2). So what are the problems Paul recognizes that he feels obliged to address? Well, distilled to a single word: meritocracy.

Meritocracy, a vertical hierarchy “in which the talented are chosen and moved ahead on the basis of their achievement[3]Definition of MERITOCRACY. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/meritocracy. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021.,” finds itself in Paul’s sights throughout the introduction and first chapter primarily because of what it can and cannot account for. Chief among his list of grievances with the ideology: “Meritocracies lead to bad outcomes and perverse incentives that privilege the few over the many. When it comes to video games, widespread meritocratic norms lead the successful to believe their victories are solely accountable to their skill and effort, which can preempt efforts to help other people.” (25) Meritocracy is principally a power structure, a dominance hierarchy, in which those at the top, by recognition of their supposed merit, have power and agency over those below them. It’s not enough to win and lose in a meritocratic system; winners are often given positions of actual power and control over “losers.”

The first Western thinker to put meritocracy-as-such into the public consciousness was someone who vehemently opposed it. British sociologist Michael Young published The Rise of the Meritocracy in 1958, intending to skewer the idea as he coined the term; this backfired, and “meritocracy” ended up fueling the fires of the international managerial class for the next four decades.

I have been sadly disappointed by my 1958 book, The Rise of the Meritocracy. I coined a word which has gone into general circulation, especially in the United States, and most recently found a prominent place in the speeches of Mr Blair.

The book was a satire meant to be a warning (which needless to say has not been heeded) against what might happen to Britain between 1958 and the imagined final revolt against the meritocracy in 2033.

Much that was predicted has already come about. It is highly unlikely the prime minister has read the book, but he has caught on to the word without realising the dangers of what he is advocating.[4]Young, Michael. “Comment: Down with Meritocracy.” The Guardian, 29 June 2001, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2001/jun/29/comment.

As Paul explains, the idea behind meritocracy has existed for centuries, often as an alternative to hereditary rule and caste systems. But wherever meritocracy has been tried, a problem has arisen: once people obtain power based on their merit, they tend to want to keep it and pass it on to their family, rather than let the meritocracy replace them with a new cohort of meritorious individuals. “Meritocratic norms become more prominent in a rebellion against the aristocracy, but those meritocratic practices eventually end up producing their own aristocracy,” Paul writes (31).

Historical examples of meritocracy “offers two key lessons to video games,” according to Paul.

First, meritocratic systems fall apart when they stop measuring merit and focus on elements tied to inheritance. For video games, this can be seen in limited game offerings and a desire to produce more of the same, rather than games that are new and different, as success is determined by prior experience rather than the results of a fresh examination. As Robin Potanin argues about the practice of game developers, games are made for preexisting audiences, not wholly new ones.

[…]

Second, meritocracy is a powerfully attractive idea that quickly co-opts those who are successful into defending the status quo; finding a position from which to critique the system is exceptionally difficult. Even for those who see deep-seated problems in game culture’s current state, tracing the cause to the design of games is difficult because it implicates everyone involved in the production and consumption of video games. Players who find success at games are more likely to keep playing, and the developers and publishers catering to that audience are more likely to find funding for their next title.

(Page 32-33)

While Paul says that meritocracy co-opts the successful into defending it, this only tells half the story. The unsuccessful in a meritocratic system are also given incentives to defend it. This is because meritocracy atomizes failure and hides structural causes of inequality; if you weren’t successful at getting a job or beating a cohort of PVP players in a game, have you considered… trying harder? In other words, git gud. This mindset permeates video games. Paul mentions a particularly fascinating situation in which an Overwatch player attempted to be the worst player on purpose.

Dale Brown, aka “Bacontotem,” wasn’t particularly great at first-person shooters, but was still good enough to be in the lower-middle tier of Overwatch‘s ranking system. According to a profile of Brown by Nathan Grayson, Brown is quoted as saying, “It dawned on me one day: Your average medium-skill person’s probably going to be trying to show off, get started on Twitch, and everybody’s going to be following all the high level players because there’s just going to be a natural audience for them. I got curious: what’s going on down at the bottom? I’m sitting there thinking, ‘I’m not that great at these FPSes. Let’s go see how bad it gets.’”

Grayson wrote:

Overwatch’s season one skill rating system was never intended to be a straightforward progression. Through hard work and diligence, you could slowly, painstakingly gain a fraction of a rank, but if you lost even a couple times in a row, you’d almost certainly take a nasty spill down the skill rating ladder. Ultimately, the system was meant to balance out. You were supposed to move up and down within a general ballpark of numbers. Blizzard didn’t do a super great job of making that apparent, though. As Brown observed, that led to players with chips on their shoulders and burning mounds of salt in their hearts.

“In the mid-30s, I met the angriest people in the world,’ Brown said. “It’s somewhere in that mid-30s and upper 20s [area], these are just the angriest people in the world. They think they should be doing better and they’re really not good enough, or these are just people stuck on really bad streaks.’[5]“The Guy With The Lowest Possible Rank In Overwatch.” Kotaku, https://kotaku.com/the-guy-with-the-lowest-possible-rank-in-overwatch-1785662123. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021.

This rings true to me. During my three-year stint as a Destiny 2 player, I dreaded playing PVP. It isn’t fun to constantly die, get back up, die again, get back up, and die a third time – all while having your rank compared to others stuck in your face like you’re a dog who had an accident on the carpet. There wasn’t a way out; not doing PVP meant I was falling farther and farther behind my friends who were slogging through it for good guns, while doing PVP never failed to absolutely drench me in salt and, on top of that, I wouldn’t even get the good guns. When you’re bad at a video game, or even just one aspect of a video game (non-PVP activities in Destiny 2 never gave me any trouble), you absolutely get a feeling like something is wrong, but that feeling is always redirected back to you, the player with a deficiency. Paul recognizes this.

“The system strips out systemic critique as a possibility because the whole point is evaluating the individual,” he writes (38). “When you are assessed as an individual, it is hard to engage with feedback when meritocratic ranking systems consistently remind you of your failures.” At the same time, successful players are encouraged to “forget about the structural advantages that help them succeed.” (39)

Think about this: can you name a mechanical difference between Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, The Division 2 and Destiny 2? How do you fire your weapon in those games? How do you aim? What structural barriers exist that keeps a player who is proficient at, say, The Division 2 from doing well in Call of Duty? Much of a player’s skill can be transferred from game to game, which allows them to rise up the ranks much faster than a new player or one that can’t spend a lot of time playing games. And okay, sure, you could make an argument here that this isn’t a bad thing. The less time you spend in the onboarding process to the game, the better. Plus, hey, the better players are from the start, the more interesting and competitive the matches, right?

I mean, I guess so. But it doesn’t make for very inventive game design – especially if games like Call of Duty are the main types of games getting made. Paul highlights this as a structural problem endemic to meritocracy. “Video games are constructed by people who are already part of the community and are invested in making games for the people who already play video games,” he writes. “Instead of developers branching out in new directions, a risk-averse approach to game development and a lack of diversity in the community of people making games creates an echo chamber where recycling content and ideas ensures that those who are part of the community already are rewarded and their success is justified under the guise of merit.” (48)

I think there’s a fine line between simply defining a game genre and identifying the areas where specific games share a substantial amount of design with each other. Games within a genre are of course going to be similar. But I think the point Paul is trying to make here is not that “games are similar = bad,” it’s that there are structural reasons why so many of these games within specific genres are as similar as they are – and that meritocracy actively prevents players and critics from interrogating those structural reasons. From there, Paul extrapolates to other concerns, like the prevalence of class struggle, racism, sexism, homo- and transphobia, and ableism within games.

Merit in video games is assessed by the time a person has been able to invest in learning this game and all the similar games a player has played before. Being successful in a game depends on the economic ability to pay for games and systems, the cultural permission or encouragement to play games, and the good fortune to find game narratives, characters and genres that are at least somewhat relatable or interesting. As Adrienne Shaw established, the representations chosen in media matter, as what is selected for representation ‘provides evidence of what could be and who can be possible.’

(Page 53)

Imagine that all you’ve ever eaten is lasagna. All your parents ate was lasagna, and their parents before them only ate lasagna as well. They’ve taught you how to make a mean lasagna, and you’ve spent years perfecting your craft. If someone asks you how to make a lasagna, you can lead a master class. You compete in different lasagna-making competitions and as they’re handing you gold medals, the judges tell you that you objectively make the best lasagna in the world. Making lasagna is a difficult and time-consuming task, so you view your wins as hard-fought and well-deserved. People tell you that you should start a restaurant so that more people can indulge in your exquisite lasagnas.

But… what happens if someone asks you to make a salad to go with the lasagna? The questions running through your mind would probably be, “what the fuck is a salad?” or “how do I make a salad?” or even “ugh salads are disgusting, is this even food? There’s no ricotta or sauce or pasta.” The existence of lasagna doesn’t preclude the existence of other food and vice versa, but the narrow scope of your experience – in exclusively making and eating lasagna – makes it difficult to incorporate the experiences trying other foods can bring. If your only frame of reference is lasagna, you will undoubtedly judge other foods based on that frame of reference. Similarly, you might feel like your way of life is under attack if someone suggests that eating nothing but lasagna is bad for you or asks to make modifications to your lasagna recipe, and you may not understand why someone would say stuff like this.

This analogy, like all food analogies, is limited. But it serves to illustrate a couple points: meritocracy reinforces structural inequalities at every level. It mandates and encourages specialization while disincentivizing experimentation. It leads to the formation of odd biases against other ways of doing things and makes it difficult to critique the status quo because individuals see personal stakes in upholding it.

Paul believes that this self-reinforcing system serves to do a few things: it “foreclose[s] critical thought,” limits the audience for specific games and creates animosity between skilled players and unskilled players. “The lack of ability to empathize or think beyond one’s circumstance is a hallmark of the problems with meritocratic discourse and a key driver of the toxicity of game culture,” he writes. (61)

From a consumer perspective, the question of a “toxic” meritocracy in games culture presents some problems to us that we can’t readily solve. Let’s take, for example, the argument that just won’t die: it’s harder to design women in games than it is men. We’ve seen this for literal decades, from the tiny 8-bit sprite era to Escape From Tarkov. It’s patently untrue, but it’s very persistent. Wrapped up in this argument is assumptions about audience demographics and what that presumed audience wants and how this particular design choice will be perceived by this presumed audience, to say nothing of the types of games the designers have played, whether they have women (or queer people, or people of color…) working on the design team, and so on. Answering these questions takes more than just a consumer movement saying “we don’t want this kind of game anymore.” It also takes the cooperation and evolution of the dev teams working in the industry to make changes. As Paul demonstrates, this might be easier said than done.

Right now I’m thinking about how convincing Paul’s argument against meritocracy is. The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games thus far has described what it means by meritocracy, and Paul has given reasons why he believes it’s bad. It’s convincing to me, in the sense that I don’t really need to be told that many vertical hierarchies, including/especially those which reinforce the status quo, are bad; I believe it already. But so far he’s been pretty light on alternatives to meritocracy as it pertains to games culture, or solutions to the problems meritocracy has caused. Maybe it’s unfair to expect them.

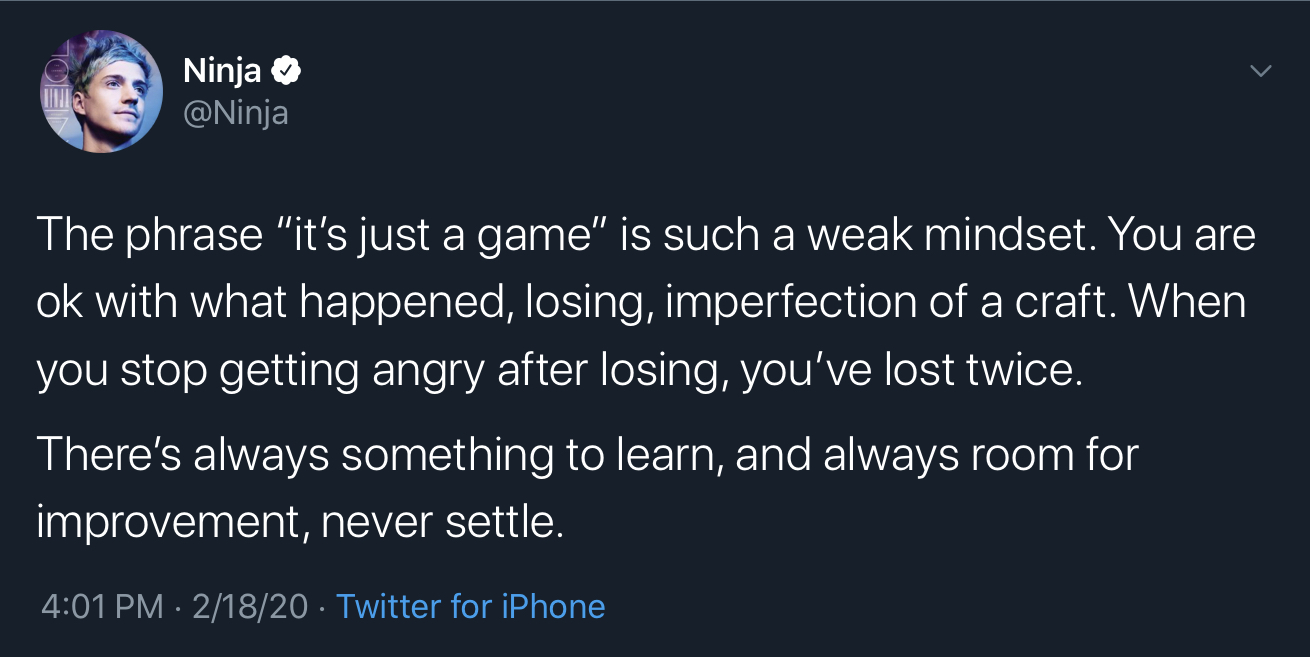

What I can say is that it’s not too difficult to see where Paul is coming from when he talks about meritocracy as a self-reinforcing system that compels people participating in it to defend and sustain it; the review examples I listed above, in the first section, illustrate this nicely. Even Tyler “Ninja” Blevins’ tweet about “it’s just a game” being a weak mindset (the featured image) shows us an example of toxic meritocratic thinking.

Paul’s next chapter concerns itself with a meta-analysis of game studies literature that talks about toxicity within player circles. So who knows – maybe we’ll find the answers to our questions – and more – there.

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

References

| ↑1 | Book Review: The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games – First Person Scholar. 26 Sept. 2018, http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/book-review-toxic-meritocracy/. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul, Christopher A. The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games: Why Gaming Culture Is the Worst. University of Minnesota Press, 2018. |

| ↑3 | Definition of MERITOCRACY. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/meritocracy. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021. |

| ↑4 | Young, Michael. “Comment: Down with Meritocracy.” The Guardian, 29 June 2001, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2001/jun/29/comment. |

| ↑5 | “The Guy With The Lowest Possible Rank In Overwatch.” Kotaku, https://kotaku.com/the-guy-with-the-lowest-possible-rank-in-overwatch-1785662123. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021. |