Coming in before the end of 2022, we are finally at the end of our journey, the last deep-dive into Umurangi Generation, the best game of 2020. This article is going to spoil The Depths and Underground City. If that’s not something you’d rather interact with, move along. Go play Umurangi Generation instead of making your dislike of spoilers my problem, it’s on Game Pass, Steam and Switch and is well worth your time.

Here are the previous posts in this series: Part One. Part Two. Part Three. Part Four. Part Five.

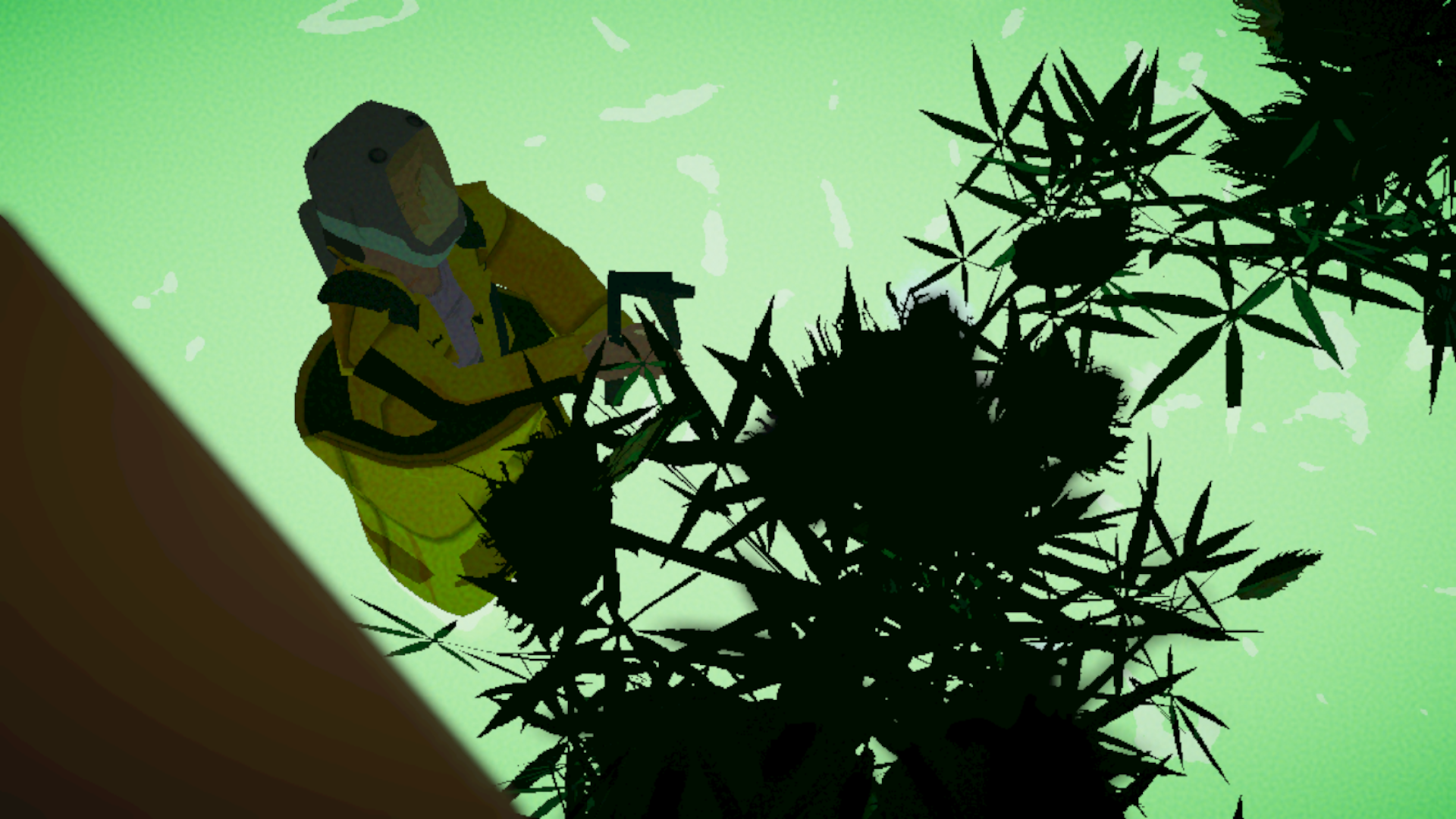

Unlike some of the other locations we’ve visited, The Depths feels like something out of BLAME!; a sewer level that sprawls vertically instead of horizontally, is easy to get lost in, walls full of art and graffiti, UN shelter tents everywhere. This is an uninhabitable place that has been forced habitable purely because there is nowhere else for these folks to go. Punks and ravers mingle among disabled veterans of the human-Kaiju war. Someone has retrofitted a full-service bar into a shipping container next to a full armory next to a laundry facility next to a medical tent advertising a service to “cut a lump off.” Is this a criminal underworld, a homeless encampment, an anarchist commune, an edgy teen hangout spot? Yes. It’s likely that most of what we see down here is stolen. This is the face of resistance to the UN’s fascist reign.

So what are we doing here? In previous entries we have ruminated on the Courier’s proximity to power, how we are able to be present at spots like Contact and Gamers Palace as a simple courier. The question now is: how are we able to reconcile that proximity to power with our access to this node of resistance? In the game, we are never told who our photos go to. We don’t see newspapers or blogs or the government run our work. We can play our game as though we definitely aren’t snitches, but I have had my doubts this entire time. Photography can alert the people to great injustices being committed in their name, but it can also serve as a method of sousveillance, spying from below. We can’t be neutral in this regard, as much as one might desire that neutrality.

The mood in The Depths is pensive. People are standing around, arms crossed, looking like something is about to happen. And we know that there is, that two weeks from now the world is going to end for everyone, but there’s no way to relay that to the people here. Would it change anything if we were able to warn them, anyway? My guess is, it wouldn’t do shit. Even if you know the end is coming, even if the fight is no longer “worth it,” you still have to do it. If not for the slimmest chance that a better world is actually possible, then at the very least on principle. We might all be on the way off this mortal coil but we still shouldn’t let the fascists know a single second’s peace.

In a literal sense, The Depths is meant to signify what martial sacrifice really looks like. All the “brave heroes” of yesterday and today’s wars, the troops we make a show of supporting while they’re getting blown up just off-screen, end up in a metaphorical sewer. The state chews up and spits out with impunity, leaving broken people behind to fend for themselves on all sides of a conflict. The UN regime in this instance is particularly callous and cruel. Is it any wonder that the folks down here are organizing, arming themselves and creating a zone of mutual aid?

“Don’t take close photos of protestors’ faces.”

The Underground City, beneath the Tauranga suburb of Gate Pā, has become a vortex of tension and possibility. Historically this site is significant: in 1864 Ngāi Te Rangi fighters routed British soldiers here in the “worst defeat the British suffered” during the New Zealand Wars. In this level, peaceful protestors gather wearing masks, holding umbrellas and flags that say “UN Out,” carrying spray paint with which they scrawl their grievances on any and every surface. The protest space is hemmed in on all sides by retaining walls, some kind of energy barrier, and the boarded-up shops on either side of the street. Concrete barricades meant to break up marchers litter the asphalt.

“Don’t take close photos of protestors’ faces.”

The Courier’s role has shifted here. Instead of taking photos to deliver to a specific client, we are shooting directly for social media. We take a hit to our metrics every time we shoot a photo of a protestor’s face. It’s a social solution to the problem of sousveillance, as people watching us watch this protest don’t take kindly to breaking individual protestors’ opsec. As we mill around the protest, we have to be intentional in how we compose our images. Photos from above are fine, as long as they don’t linger too long on any one person. So are extreme wide angles and telephoto shots. There are so many interesting things in this stage to take photos of, aside from the context of the area, that it can be tempting to break the rule. But we must insist:

“Don’t take close photos of protestors’ faces.”

After you collect all of the bounties for this level, the protest escalates. A Peace Sentinel shoots up from the ground, looming ominously above. Riot cops move in shooting tear gas at the disoriented demonstrators and beating them with truncheons. On the surface, one might surmise that this level is supposed to represent “resistance to fascism.” As we experience the devolution of the protest into police brutality, the first time one of these levels has been truly in-motion by the way, it functionally isn’t any different from real life. State repression is state repression is state repression, even if the state doing the repressing puts on a liberal mask.

“Don’t take photos of protestors’ faces.”

We are beaten unconscious by a riot cop. We come to on top of a building after the Peace Sentinel has enforced peace on the demonstration. Looking down, the protest area is nothing but a crater. The UN is going to charge Tauranga $2,273,282,281.38 for this single protest. But we— we are alive, and we are with our friends. And as we take our final selfie, that must be enough. We must be grateful. Tomorrow’s still coming.

The end of the line.

There is so much more to say about Umurangi Generation. My perspective is limited to my experience, and with a game like this, I simply can’t speak for all possible viewpoints on it. So I want to issue a challenge: engage with this work critically. Tease it apart. See what you can find. Tell us about your experiences. Rewrite the narrative, make this series obsolete. Barring that, read these other writers:

Jeremy Signor: Umurangi Generation and Bearing Witness

Dan Taipua: What a video game about a futuristic Tauranga can tell us about our present

Natalie Clayton: From graffiti to giant robots, Umurangi Generation’s Macro DLC isn’t messing around

DEEP HELL SKELETON: Quarantine Games: Umurangi Generation

Ryan Stevens: FINAL LEVEL: Climate Disaster in Umurangi Generation and Sludge Life

A Luke to the Past: How Umurangi Generation Avoids the Tourist Trap

Florence Smith Nicholls: Picture Imperfect: Photography, Dark Tourism and Video Games

Ruth Cassidy: Urgency and Mastery in Umurangi Generation

Emma Goehler: On Bad Endings: Resistance and Meaning-Making in the Apocalypse

Andrew King: Propaganda in the Bunker

Chris Franklin: Vibing to the End in Umurangi Generation

Static Canvas: How Umurangi Generation Tells a Story

Super Bunnyhop: Umurangi Generation, Colonialism, UAPs, UFOs and Alien Invasion Stories

Response

[…] The Discontents: Umurangi Generation, Spoiled Part Six – No Escape Kaile Hultner caps off their tour of their 2020 game of the year. […]