There’s a point where Chorus (stylized Chorvs) begins to grip you. That point is probably situated at different places for different people, but for me it was about ten hours in. I had just finished helping rally a group of pirates together to join the so-called Enclave Militia, and in addition to that, I had re-learned my first “Rite” – the Rite of the Hunt. This power allowed me and my ship – a telepathic F-35 named Forsa, short for Forsaken – to teleport behind enemy spaceships and more easily take them out.

Suddenly all the hours of banging my head against the wall in missions with inscrutable objectives, of dealing with insufferable 90s-to-early-2000s-era SciFi Network dialogue, of suffering through the handful of bugs that, while not frequent, hit hard – it was all worth it. For a fleeting moment I was “one” with my ship, pulling off wild astronautic maneuvers, shooting a half-dozen enemies down within the space of a few seconds, feeling like Mihaly was portrayed as flying in Ace Combat 7.

And then, just as fast as the feeling of connection washed over me, it was gone, and I was back in the goofy, messy spaceflight and astronautical combat sim that Chorus really is.

Chorus centers on Nara, a former warrior-priest from an oppressive cult-slash-empire called the Circle. Nara is in exile, hiding from the Circle in a backwater haven for freethinkers called the Enclave. One day, the Circle attacks the Enclave, and Nara realizes she can’t run from them – or her dark past – any longer. If you’re thinking “This sounds an awful lot like Star Wars,” you’d be right, it’s just like Jedi Starfighter – only, instead of the Jedi being the dominant force in the galaxy, it was the Sith.

Most of the game revolves around Nara puttering around the galaxy in Forsa, looking for relics and shrines that will allow her to regain her powers. In Circle society, Nara was a Marked One, an Elder; in layman’s terms, she possesses immense psychic powers and had ritual sigils tattooed onto her that allow her to manipulate those powers in specific ways. Her innate power, “Rite of the Senses,” allows her to sense the “life-force” in or on objects, which gives her an edge in terms of tracking items and people. “Rite of the Hunt” is the teleportation power; “Rite of the Storm” directs a bolt of lightning at a ship to disable shields and other electronics; and “Rite of the Star” allows Nara to move quickly use Forsa as a battering ram.

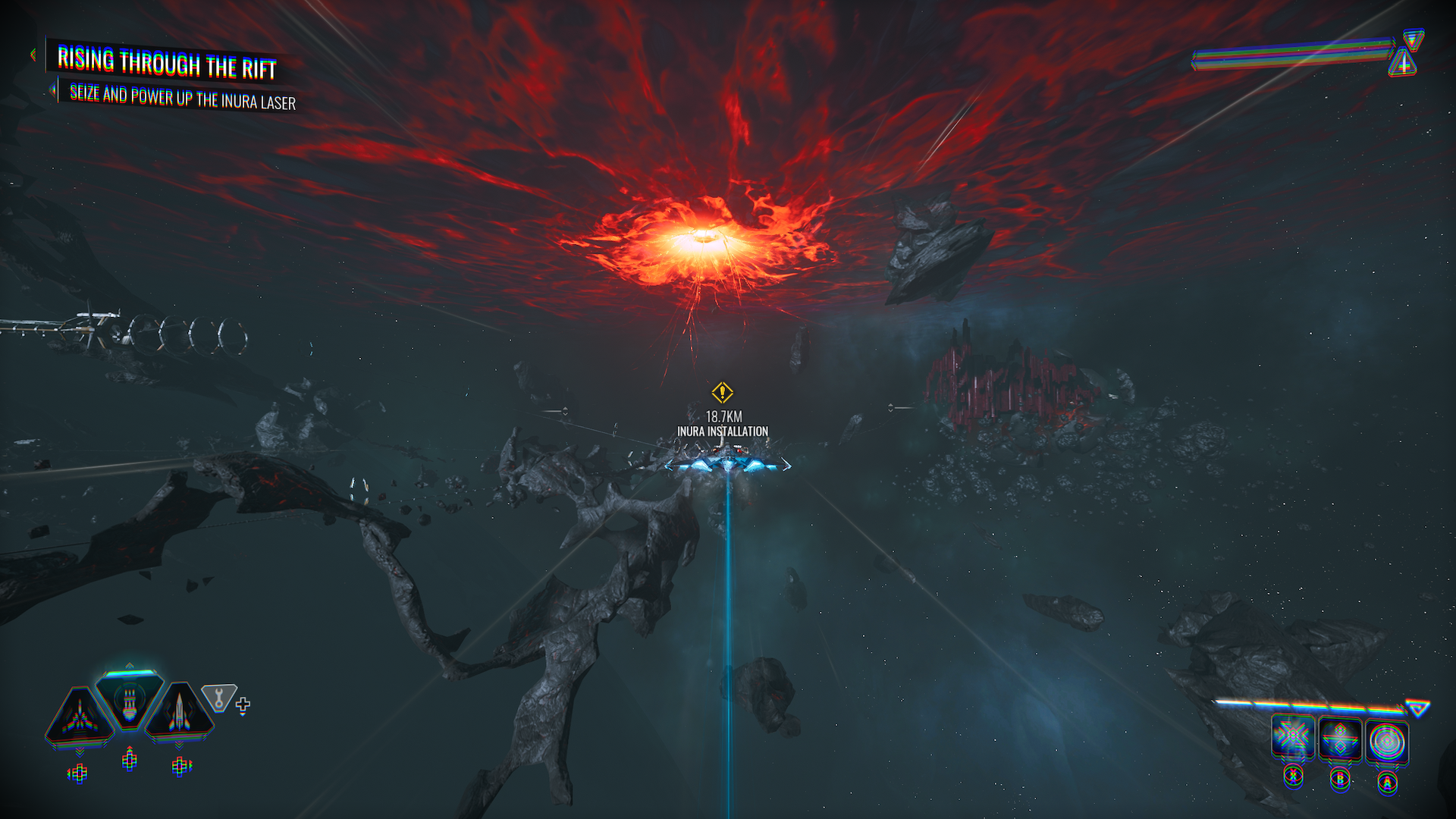

Why are we looking for shrines, then? Because Nara burned all of her rites off (aside from Rite of the Senses) after creating something called the “Nimika Rift,” a planet-cracking superstorm of evil energy. This incident is what caused her to run and hide for seven years; we’re looking for the shrines again because we want to destroy the Circle.

There’s a lot of this kind of easily-digestible narrative in Chorus, and it’s tempting to say that it doesn’t really matter, but without this plot veneer, there’s not much else to do in this world. There are a handful of sidequests per unlocked area, and most of them tie back in directly to the story anyway. And when those quests are done, they’re done. The area is now empty, until a story mission necessitates your return.

This, uh… economic storytelling contributes to a nice sense of motion where nothing ever truly overstays its welcome, but the world is also kind of thin. Here’s the thing about that, though; if you treat Chorus like one of those 90s/00s-era SciFi shows, it does all work. I found I could much easier suspend my sense of disbelief by thinking about the game in this way. And more to the point, I found myself more willing to power through some of the more frustrating missions and dogfights, just to see what ridiculous nonsense was sitting on the other side. In this sense, I was rarely disappointed.

Still, I know this is damning with faint praise: “Oh, the game’s really good if you ignore all the stuff that’s bad about it!” And it really is more than that, all told. The game is gorgeous and highly stylized, flight controls are responsive, going from place to place isn’t a chore, and you can tell the game devs were thinking somewhat critically about the world they were creating. There are surprising moments where the game tackles ethical questions I didn’t think it would go for, and beneath it all is a pretty compelling-if-standard quest for personal growth on Nara’s part.

There are elements of better games here that don’t work quite as well as in their original titles: a dash of Control’s paranormal power- gathering, a hint of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice’s tortured inner monologue and head tattoos. The Faceless, the game’s true enemy, is essentially the Hiss mixed with the Sith’s whole “bad emotions make you more powerful” thing. It’s video games, 100 percent. Despite all that there is and might be to gripe at, the fact remains: I spent about 20 hours playing and beating this game, and I don’t regret that time spent at all.