There will be spoilers for this game. Play it first or don’t.

When I first played Shedworks’ Sable, I was awed by its mysteriousness. As Sable wanders through the desert toward the next stage in her coming-of-age trial, there’s a chance for her to come across one of a number of ancient ruins. These ruins, the desiccated remnants of downed colony ships, contain still-readable fragments of black box data from the crash that stranded her distant ancestors on this planet long ago. Learning all of this isn’t strictly-speaking necessary to complete the task in front of us; it isn’t a game about “fixing” the world, and there are no grand plans put forward for escape. But it absolutely deepens our appreciation for the world as it exists, and all the different people making a workable life out of the harsh environment.

Similarly, in Kojima Productions’ Death Stranding, a game defined by exploration, discovery and the forging of connections, each time Sam Porter Bridges connects another node to the Chiral Network we learn more about the world post-Death Stranding and how exactly America devolved into the scattering of sparse outposts and shipping centers we interact with. In this case, the knowledge is usually instrumental to our progress, for weapons and other craftable items, but the result is the same. As we travel our inbox fills up with all the people we’ve come across wishing us well and providing us with insight. It’s a great example of a game where the journey is the destination.

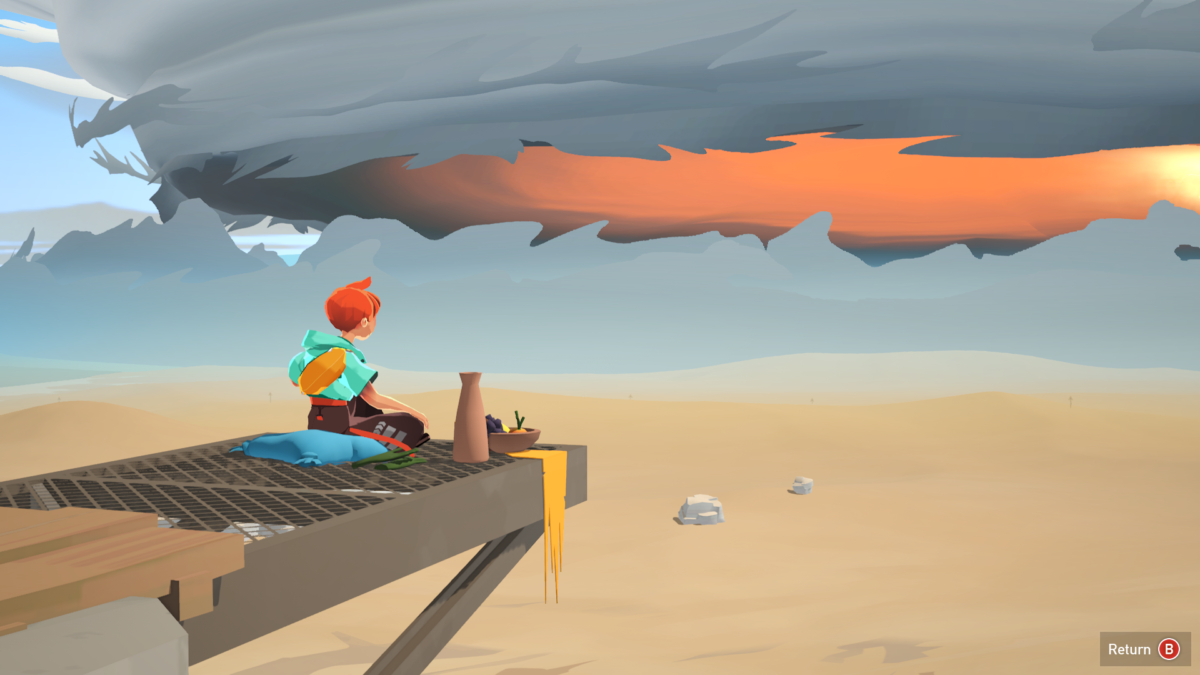

Studio Plane Toast’s Caravan SandWitch aspires to these experiences. You can feel it from the moment main character Sauge steps foot on Cigalo. The environment is littered with Stuff™ to explore, as far as the eye can see. You dutifully engage in the tutorial, reintroducing yourself to the residents of Estello Village and visiting Rose, the old woman who lives on the village’s outskirts with her little garden and her animals. She lends you her old caravan, a giant research truck with the ability to wield certain gadgets, provided we have enough components. This is a game that, from the start, wants to set us up right.

Reviewing a game like Caravan SandWitch is tough. You want to unequivocally love it. It’s an indie studio’s first project. It starts as a shining example of the ever-elusive strand-type game. It looks wonderful. It feels good to explore the sandbox. There are interesting characters here with stories that compel you to keep moving forward just to learn more about their whole deal. You want the game to stick the landing, nail the ending… and then things suddenly fall apart. Caravan SandWitch is a game that feels like it squanders the ending it earns, and unfortunately this keeps it from being great.

(You Can’t) Go Home

Like Death Stranding and other games in this vein, Caravan SandWitch starts with the premise that connections once held dear have degraded over time, or even been broken. Sauge is a former resident of Cigalo who moved away from the planet after her sister disappeared. She’s only back now because of a distress signal from her sister emanating from the planet. During the six years between moving and the events of the game, Sauge joined the Consortium’s pilot training program. Because of what the Consortium is, and what it represents to the people of the planet, this automatically puts Sauge at an even further remove from them. Therefore much of the early game is spent reforging those connections with the Reinetos (froglike people indigenous to the planet) and the residents of Estello Village…

…Is what I would say if you actually spent that much time doing that. Instead, for most of the villagers, Sauge’s departure and signing up as a pilot with the Consortium is considered at worst a mild annoyance. Instead, the villagers throw a party celebrating her return, giving her a chance to talk to everyone separately and say “sorry for leaving!” This moment had me going “sure, fine, whatever.” It’s okay for a game with a six-to-eight hour runtime not to have deep, dense conflict built in to every single moment, and besides: Sauge is a kid. Six years in her past puts her at, like, eight years old at most? Who is realistically going to blame a child for leaving when that likely wasn’t even her decision to make?

But still, something about the blasé nature of this whole segment of the game felt off to me. At first I attributed it to poor localization, which I still think is the case for some of the writing’s stiltedness. As I kept playing, though, I kept noticing this same dynamic pop up over and over again. Here it is, simplified:

Character 1: “I used to work for the Consortium!”

Character 2: “Oh no, that’s bad!”

Character 1: “But I left because I didn’t like them.”

Character 2: “Oh, okay!”

[END SCENE]

Like, it’s not even that someone who used to work for what is essentially the military-industrial complex can be forgiven or accepted in a community that opposes said complex that I’m having a hard time with here; it’s the abruptness of it all, the fact that nothing is ever so fraught as to be even a little bit unacceptable.

Maybe it’s because everyone else has other shit going on.

Solving Problems, Making More

Cigalo’s got problems from the get-go. Someone set up signal jammers all over the place, making communication across distances impossible. As we wander around disabling these jammers, more of our map unlocks and we’re better able to keep in touch with our friends and questgivers via Toaster, which you can envision as something similar to LINE or Telegram (oddly lacking private messages, as everyone can see and comment on the sidequest requests we get). Once things open up a bit we split our time between a couple of different groups: in addition to the Estello Villagers, we have the nomads, the Reineto colony, and eventually the “Awakened” robots.

Not all groups get the same amount of screen time, but nearly every encounter teaches us something about them. With the Reinetos we split our time between a young researcher and their mother, performing two different investigations on the Consortium and the titular SandWitches, respectively. With the nomads, we help them fix equipment and prepare for a feast, and with the robots we help them process life and death as newly-sentient beings. We spend the most time learning about our friends and neighbors in the village.

All of this work learning about the world earns us components, which we use to build gadgets like a grappling hook and a signal scanner for the top of our van. This is also where most of the narrative depth of this game lies, and there’s some interesting stuff here. Project Helios – a name we see around the region – turns out to be a Consortium effort to build a Dyson cloud power plant around this solar system’s star, and they used a giant railgun – TARAASK – to shoot solar panel modules into position. The project was also massively environmentally damaging and genocidal, wiping out most of the Reinetos and turning a swampy marshworld into a parched desert.

Some Consortium engineers, sick of watching the fruit of their labor contribute to this kind of wanton destruction, sabotaged the railgun, but as they did so it caused the machine to spiral out of control. It began generating a powerful electromagnetic field that caused an “infinite storm” to brew around it, unfortunately resulting in mass casualties. This got the Consortium to leave Cigalo, but only because fixing the TARAASK was more expensive than bailing. The engineers who sabotaged the machine exiled themselves from the remainder of the colony and began calling themselves SandWitches, vowing to defend the infinite storm and keep the Consortium from reaching the planet’s surface again, by any means necessary.

Learning this history, we become aware of the cycle we’re now a part of, where people just sorta do shit without consideration for how their actions will affect others – or how they themselves will be affected. The SandWitches put up the signal jammers, which had a negative neurological effect on the Reinetos and their connection with their mycelium-mediated ancestral history; we destroyed the signal jammers, which freed up communication for the humans and Reinetos but resulted in the death of an awakened robot whose consciousness was deleted when it connected to the broader Consortium network out of childish curiosity. We agree to help Neflè with restarting all the “receptacles” (teleporters/entry and exit points into a virtual space) because it will lead us to our sister; we don’t understand that we’re helping her get to the TARAASK’s core where she plans to shut it down, all but guaranteeing the Consortium’s return.

All of this feels like we’re being swept along the river of history, but rarely does it feel like we ever try to change course ourselves. Our nonchalant attitudes about anything and everything that happens to us, the fact that we spend the better part of two in-game weeks dallying while our sister (or what’s left of her) waits for us to find her, the way no one – even her father – seems remotely interested in helping Sauge—everything adds up to a strong disconnection between what I sense the story wanted us to take away from it and what is actually there.

The End?

There is a moment when Caravan SandWitch completely lost me, and it’s right at the end of the game. We’ve been given the self-destruct codes to the TARAASK after it becomes clear that Neflè is going to do far worse damage if she tries just shutting the machine down. The last SandWitch looks us in the eye and says (paraphrased): remember, in the coming conflict with the Consortium, individual action is never going to be as strong as collective struggle, and that we need to take their place as the first of a new generation of SandWitches.

And like, look: I agree on principle. Like, yeah, you got me! I believe in collective liberation and direct action. I think that’s a good message to put in your game! I just wish the message didn’t feel like it was tacked on in a last-second effort to conclude this video game.

It’s not that the message isn’t occasionally present throughout the game; it shows up here and there, usually when Sauge is enjoying a quiet moment with friends and family. But when it comes to missions and sidequests? She’s either working with Neflè or she’s working alone. This is a teenager plucking archives from old ruins and scavenging for water purifier parts for the nomads and looking for control terminals to help Rose keep her tomatoes watered and scrounging around for a baby’s lost rattle and getting the baker’s mail and on and on and on.

And of course she can do it. Of course she’s capable enough to do anything and everything anyone asks her to do. This is a game with no failure states, no health or hunger or damage to be taken, where you can fall from a stunningly high height and suffer no consequences and where if your van gets stuck you can teleport it back to Neflè’s garage. It’s meant to be a cozy exploration of loss and grief, I guess, where nothing too challenging ever happens, and no one ever puts themselves in a position to challenge or be challenged. And at the end: “remember to stick together if you’re gonna fight a giant corporate megaconglomerate!”

It’s lazy anticapitalism, is what it is. It’s about as bourgeois a conception of resistance as I’ve ever seen in a video game, and I played LumBearJack.

Maybe this is too harsh. There are parts of Caravan SandWitch I genuinely loved, and I think there’s a reading of this game that is likely much more charitable that looks at what it’s doing as, I don’t know, emphasizing that resistance and revolution is just as much about mutual care and tenderness as it is getting ready for a street fight. Maybe I’m just burned out and bitter and playing this twee little game about helping people out with low-stakes shit doesn’t sit right with me because I don’t see very much of that happening right now in general. Maybe I’m having a chili reaction.

Caravan SandWitch is not Sable and it isn’t Death Stranding. It is a game about reforging connections, and exploring a space to understand the past, and indeed, a game about grief and loss and how to fucking deal with that when it seems impossible. I didn’t expect to write these words, or so many of them, about this game. I think maybe the experience of playing it is valuable even if I soured on it by the end. Maybe someone could really use the reminder it gives.