Kicking in Despelote feels good. It’s a quick flick of the right stick for a light pass, but if you want to send the ball (or bottle or balloon) flying, you need to pull the stick all the way back, like priming a catapult, and then snap it forward. There’s a good _thunk_ on the hit. Kicking isn’t accurate, at least it wasn’t for me. I spent the better part of half an hour trying to knock a pile of bottles off a wall but that clumsiness feels real. After all, I’m not Messi and I’m certainly not Agustín “El Tín” Delgado.

Instead we are Julián. It is 2001, the year before the joint Korea-Japan FIFA Football World Cup. Ecuador would qualify for this tournament, their maiden World Cup campaign. Despelote is chaptered around these qualifying matches. Each match has a corresponding open-ended level set in the streets of Quito. From there it’s running around, listening to conversations, and kicking around whatever the game lets you.

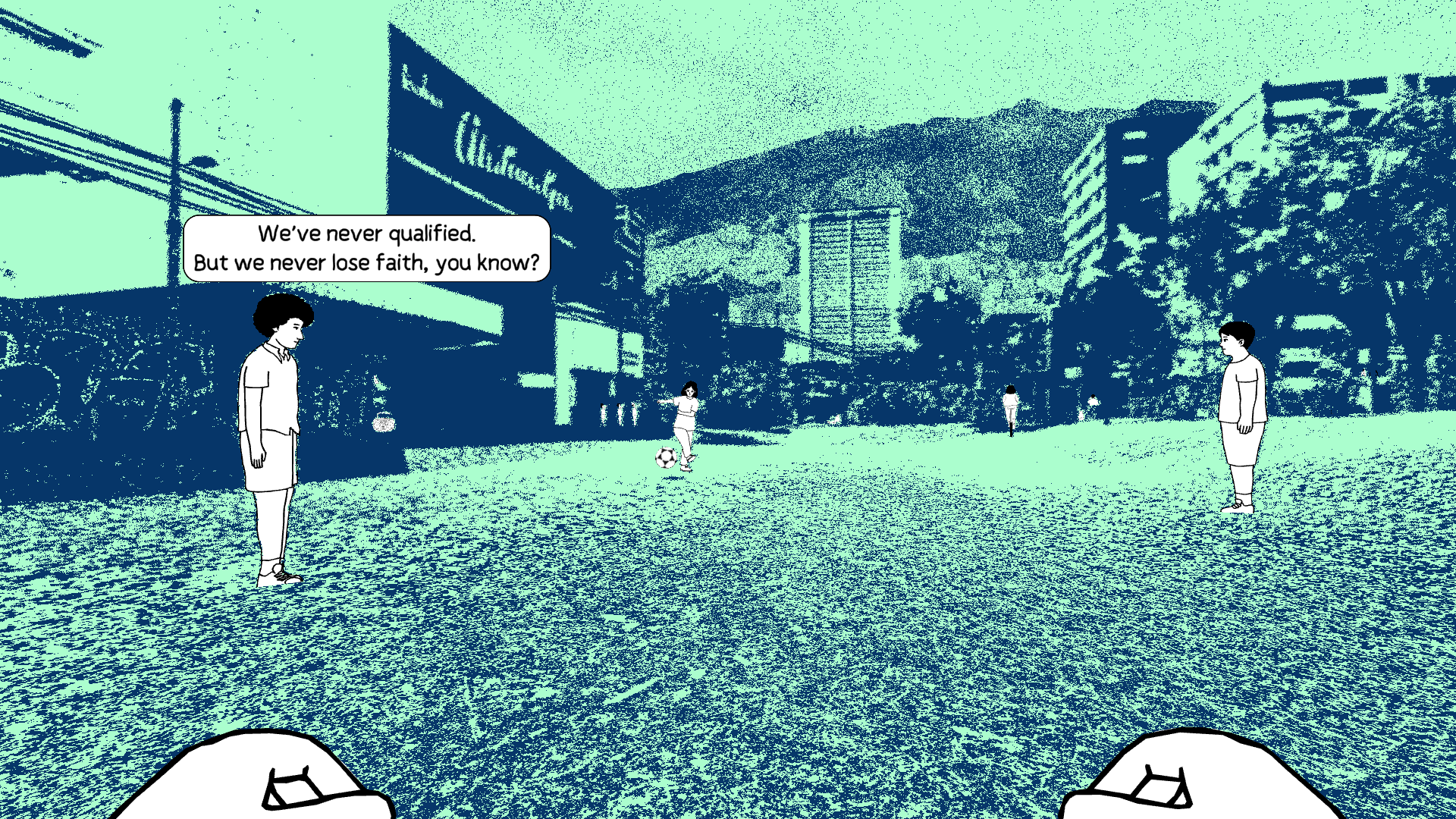

The levels are beautiful to look at. Architecture, infrastructure and furniture scanned then rendered in monochromatic pointillism. Conversely everything interactable, from footballs to posters, are rendered in a hand-drawn style. It blends together in collage like a scrapbook.

It’s a specific game about a specific person during a very specific time in Ecuador’s history. It’s a window into a country’s culture and history. It’s not a complete picture, but no media nor testimony could render the nuance of any nation. Yet the glimpses feel like reflections. Within Despelote I see my Jamaica.

When every radio station and television in a country is tuned to the same match, the same frequency, I swear to you, that you can feel it. The air is different. Your body becomes an antenna. I think this can only happen in a small country and maybe I’m stretching “small” to fit Ecuador. I can remember times in Jamaica, during the Olympics or Athletic World Championships where everyone found a Jamaica jersey or a yellow shirt, and flags adorned every car and balcony. Every television pulled a crowd. Work grounded to a halt.

I wish I could cite our men’s football team’s only world cup qualification campaign but it was in 1998 when I was only three years old. There’s relics. There’s jerseys and there’s songs. We have songs for everything. We still sing those songs.

Football, more than any other sport, belongs to the dreamers. Sure, it has its superpowers — France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Brazil, etc., who are able to wring consistency out of an abundance of resources and infrastructure, but the nature of the sport lends itself readily to upsets. Unlike most contemporary sports, football is a uniquely low scoring game. The most common scoreline in football is 1-0; a single goal. If you’re not already in love with the sport this sounds unappealing. But consider that when each goal is so precious, you just need to score one. A team that is less talented and with less resources, can steal a goal and then defend like hell. A football team can embody an underdog country’s spirit and even if it’s just on the field and even if it’s just one time, a minnow can kill a giant.

Despelote is one of the precious few games about football. EAFC (formerly FIFA) is not about football. It might be about professional footballers. Men and women are painstakingly digitally recreated down to their tattoos and gait. They never speak though. They’re action figures that you play with. There is no life outside the game’s stadium walls. The crowds are animation cycles. There are no tailgates, no vendors selling inexplicably the best soup you’ve ever had; there’s no culture. The football in EAFC emulates Football™. It is an advertisement for the sport at its most predatory. It is a celebration of the image of the ideal professional footballer — silent, proficient, non-existent when they’re not dribbling.

Most football is played outside of massive stadiums and in front of crowds of tens if so many. They’re played on shared fields with half dead grass. On empty streets between goals made from leftover PVC pipes hastily picked up when a stray car turns onto the road, and then placed back, resuming as if nothing happened. They’re played after church with scuffed shoes in sweat-stained Sunday suits and with tennis balls or bottles filled with sand and dirt or just litter on the pavement while waiting for a bus. Most football is played by people not particularly good at the sport because the act of kicking a thing and watching it go is enjoyable at all skill-levels.

Those elevated matches, the ones played to full stadiums and televised to millions worldwide, are important not just for what happens on the pitch but mostly for the context that spectators bring to them.

In Despelote the matches are almost secondary. Televisions within the levels broadcast the matches, using actual footage that’s been heavily processed to the point of being barely visible yet congruent with the game’s striking aesthetic. Football permeates everyday life until it is normal. It becomes small talk in the shops — scores and performances discussed like yesterday’s weather forecast. Jerseys become the uniform of a country, and afterwards a relic in remembrance.

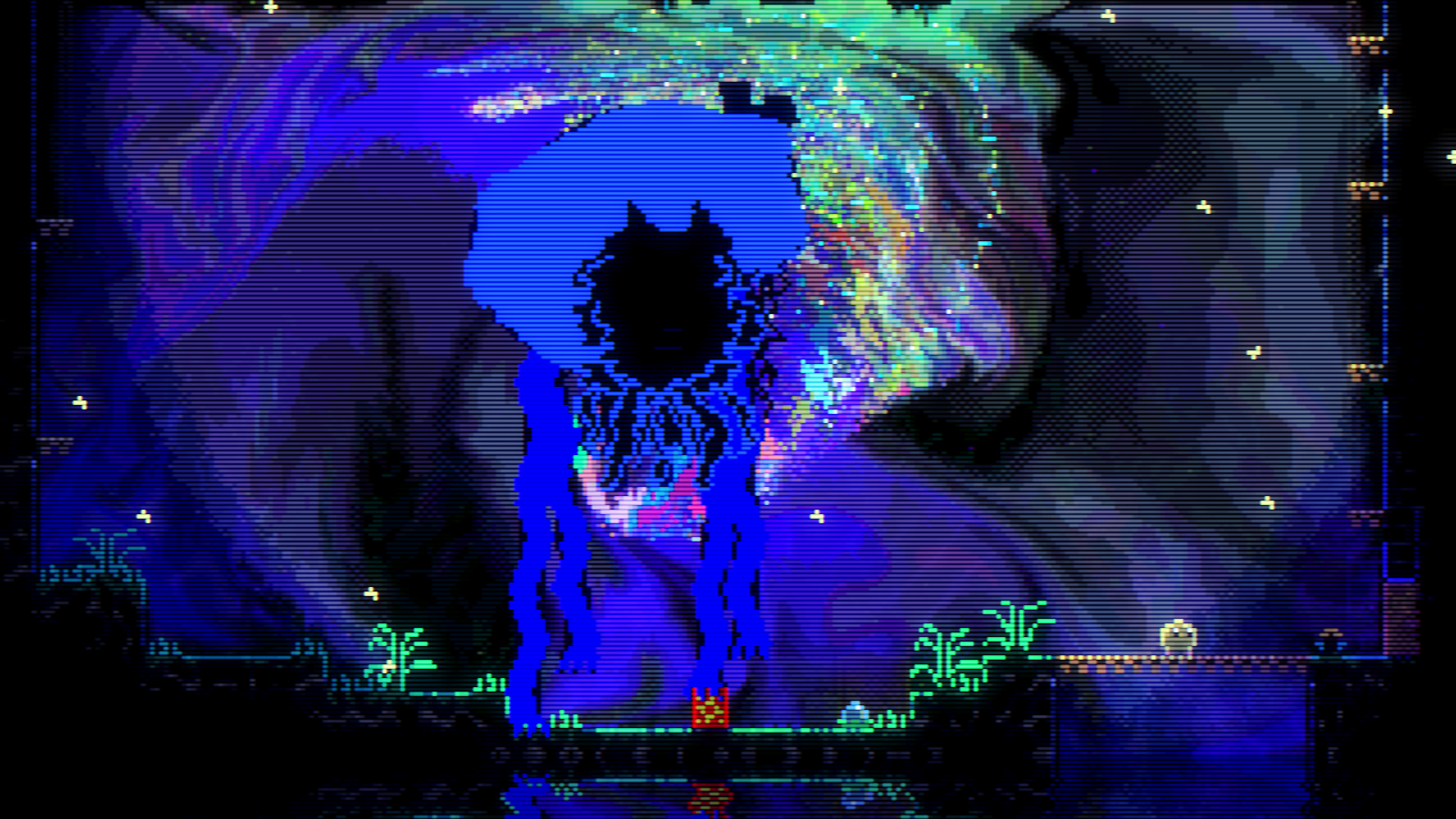

Interspersed between moments of jubilation and celebration, are vignettes that portray a more complex relationship with both the sport and with Ecuador. There’s surreal dreams of football in an empty city. Melancholic parties where Julián is unwelcome and the only thing you can interact with is alcohol until you find a ball to kick around. The relationship with his mother changes, she’s worried about him and where he’s going, both literally and regarding how his life is proceeding. There’s a longing for when the sport was simpler and for that Ecuador of his childhood; it’s a country might not exist anymore without the unifying force of an underdog national team or having gone through the relentless gentrification that plagues developing countries. Ecuador has qualified for 3 more World Cups since that run in 2001, most recently participating in the latest entry of the tournament, Qatar 2022. While by no means on the same level as South American powerhouses such as Argentina and Brazil, they are also no longer minnows. A large amount of the squad play professionally for some of the biggest and richest clubs in world football. It’s no longer enough to simply make the tournament, this is a country with expectations to make it into the knockouts and the talent to feasibly do so. The old standard has been raised.

By the end, Despelote becomes a treatise on memory, archiving, and game development. There’s an unexpected frustration in the last chapter. One that pushes past the story, and peels back the curtain in fascinating ways to reveal difficulties with developing the game, finding match footage, and depicting a nation on the brink of jubilation during the last qualifier. It all begs the question, what was the Despelote that wasn’t?

Regardless, what is here is an understanding of Football that is both intuitive yet underrepresented in the medium. The sport is not just rags to riches and luxury stadiums; it is first and foremost a game we play for fun and then a blank space for a nation, fans, a family, or just one person to project whatever they need onto it and contextualize it however they want. It means nothing and yet, at times, it can be everything.

One response

[…] Despelote review: an ode to a dream | No Escape Nicanor Gordon reflects on football as a canvas for memory, nations, and communities. […]