It’s weird to call a game in which your character avatar is climbing a massive tower “flat,” but that is what Chants of Sennaar – by Rundisc and published by Focus Entertainment – feels like out of necessity. The game’s principal mechanic is language learning, but how that works in practice bears little resemblance to actual language-learning strategies. That said, it remains an engaging and satisfying little game from start to finish, in part because “solving” a given level’s principal “language” makes you feel like you’re really engaging in a process of discovery and connection.

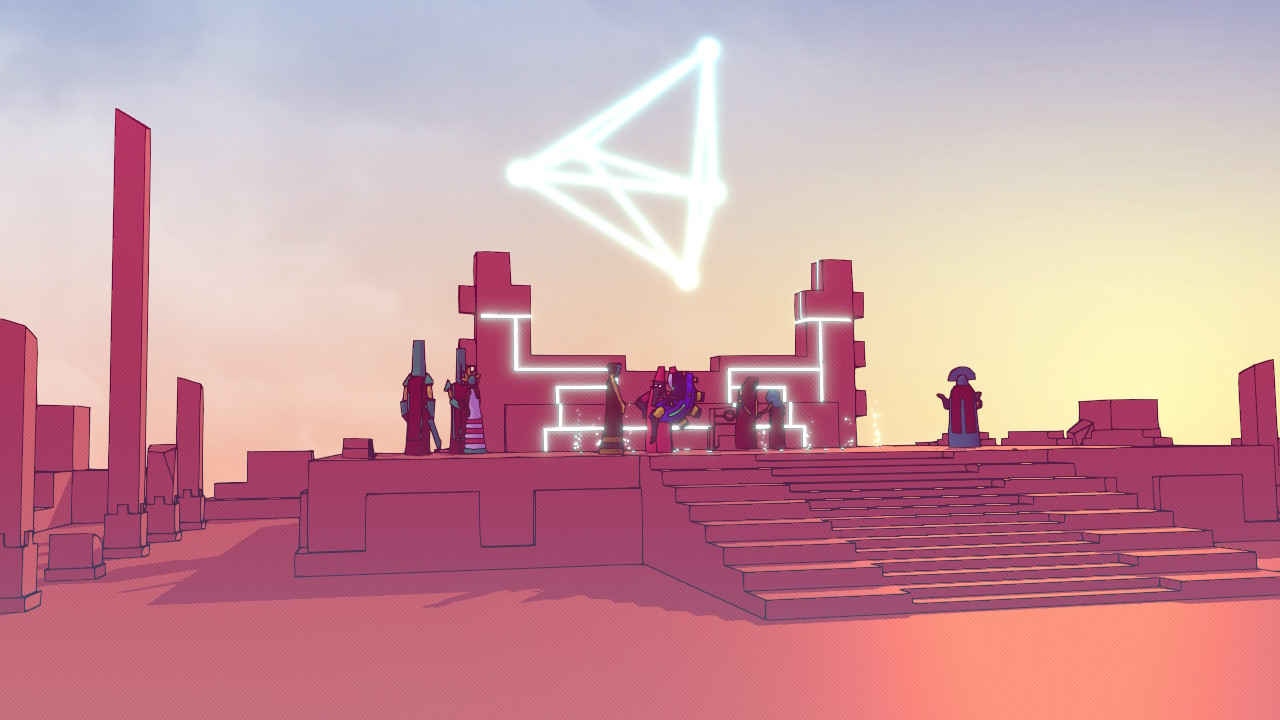

The whole conceit of Chants of Sennaar is that you are an enigmatic stranger climbing a Tower of Babel-like building armed with nothing but a notebook and problem-solving skills. There are five massive levels, each home to a different culture and language: the religious Devotees, militaristic Warriors, hedonistic Bards, pragmatic Scientists and nihilistic Exiles. Every culture has a list of glyphs to unlock, and doing so allows you to build up a kind of “working fluency” not just with each level of the Tower, but between levels as well. Think of it like you’re building a pocket “Rosetta Stone” to help you solve the mystery at the heart of the game.

Most real-life languages require a mastery of the grammar and syntax, and knowledge of at least 10,000 words, to be considered fluent. Beginners are of course beholden to much less, needing to know only about 250 words on average to muddle their way through interactions with native speakers. Chants of Sennaar heavily compresses this requirement to about 20 to 30 words per language, with a grand total – across all five levels of the Tower – of 186 glyphs. When you’ve found all of the glyphs on a given level, you’ve become “fluent,” and you can understand everyone perfectly in a handwavey “don’t look too closely at what we’re doing” sense. If you’re a linguistic anthropologist this might annoy you, but for everyone else it’s likely to be a perfectly serviceable puzzle tool.

What I find interesting is that some linguistic concepts do come into play here. For example, while most of the languages we learn roughly follow the same word order – Subject-verb-object – Bards follow a different format entirely, forcing us to think about how we transliterate words and sentences. Also, each “language” represented by their respective scripts takes on some of the cultural values of the speakers; the language of the Bards looks flowey and graceful, the Warriors use a very angular and intense script, the Scientists’ language resembles alchemical symbols, etc. We see this in actual languages all the time.

Chants of Sennaar isn’t meant to replicate language-learning best practices; it’s here to tell a single self-contained story. As a result, most of the puzzles are fairly straightforward and easy to solve even if you’re not adept at teasing out the meaning of certain glyphs right away. Other puzzles will be inscrutable until you learn what certain glyphs mean, but most of the time this can be fixed by simply talking to people you find around each level. As you have more conversations, you have a chance to collect more glyphs to learn, and eventually you’ll get a page you can fill out in your journal that associates certain glyphs with certain actions or objects. If you correctly associate each page of glyphs with their corresponding images – or if you simply guess right – they’ll lock in and you’ll just start automatically translating them as you walk around.

If you’re worried about getting softlocked or encountering impassable fail states in a game that relies on you deciphering at-first inscrutable glyphs, rest easy: Chants of Sennaar has a robust checkpointing system that means even if you fail one of the mildly annoying stealth encounters in a level, you’ll only be set back by a few steps at most.

There’s no doubt that Chants of Sennaar is a delight to play. I think if there’s anything worth criticizing in the game, it’s this: the idea at its heart is that if you can learn all of the branch languages at different levels of the Tower, you’ll be able to bring all of the different cultures together based on their shared likes and dislikes. But as you traverse each level individually, this idea is almost fully refuted by observing the prejudices and fears each culture holds about the others. For example, the Warriors won’t let the Devotees travel up to different levels of the Tower because they view them as “impure” that they must protect the “chosen” Bards from. The Bards, meanwhile, think the Warriors are idiots and the Devotees even worse. It’s hard to see how this would be “solved” by bridging the language gap, especially since the Bards have created a second-class citizen group among themselves that dreams of revolting against the ruling class. But again, we’re heavily flattening social complexity to fit in a game that can be finished in a single run. How much realism are we willing to sacrifice for the parable? In this case, quite a bit.