Borderlands 2’s Humor Evolution Was Pointed in the Wrong Direction

There’s a peacefulness to the original Borderlands that lingers with me still. By forgoing traditional cutscenes almost entirely, Gearbox’s genre-defining looter shooter featured NPCs who would only bark greetings and contextual updates mid-quest. It was a streamlining of experience so pleasurable that copycats like Destiny and The Division smartly emulated it. A story with a full cast of characters is nice, but feeling anything outside the satisfaction of watching stats tick amounted to a bonus.

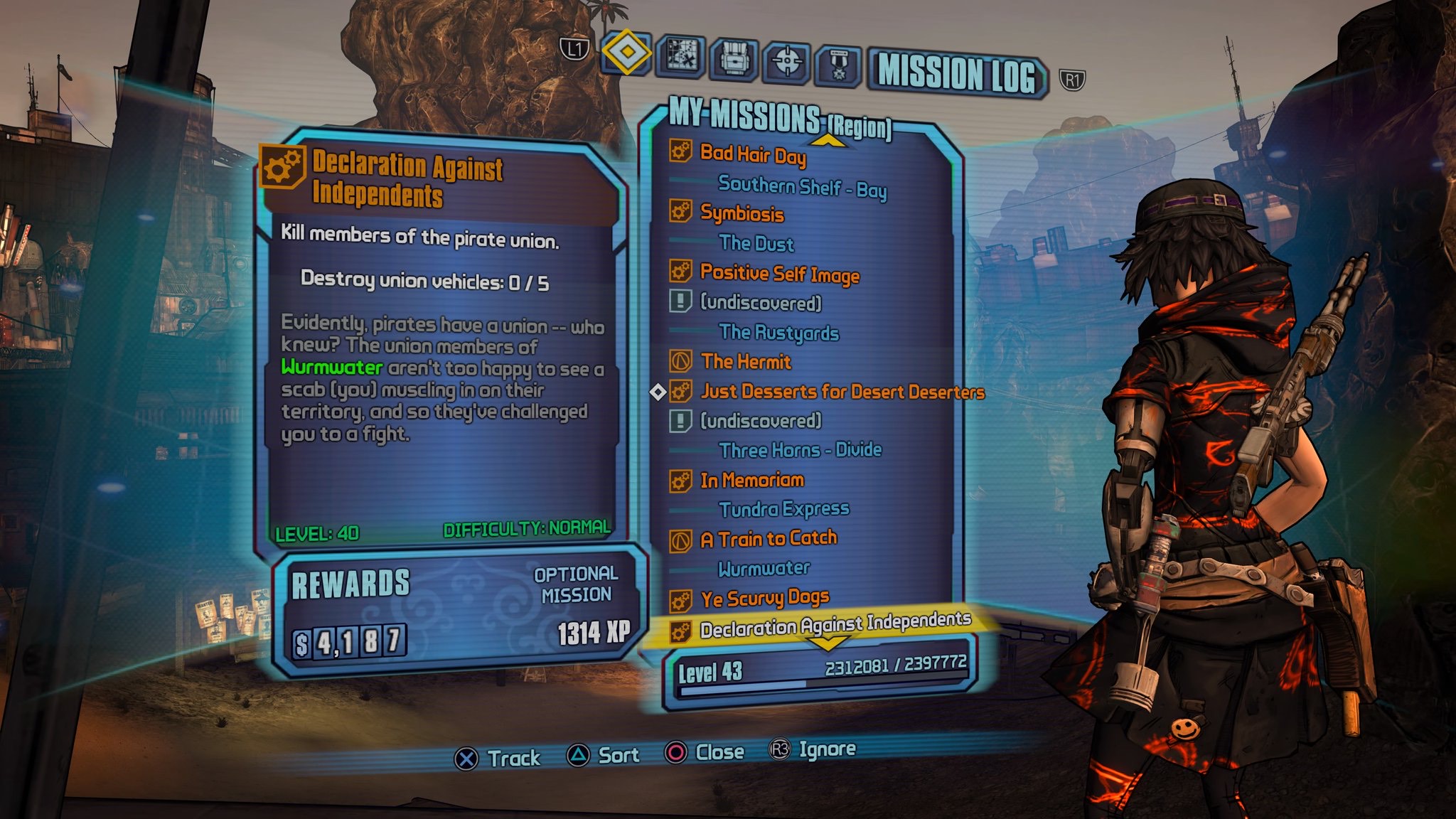

Years ago, I gave Borderlands 2 a try and was blindsided by the sheer volume of juvenile humor that always seemed to pop off aggressively during gunfights. When a stale joke returned for a victory lap–something about a “butt stallion”–I deleted the game. I never made it past the opening levels. Recently, I made the decision to finish what I started. Coming back to Borderlands 2 in 2022, I found the cloying need to entertain the player with 2000s-era reactionary stand-up every ten minutes could be traced to two especially loud characters in particular: the villain, Handsome Jack; and the de facto mascot, Tiny Tina. The noise they produce across Borderlands 2; its most popular DLC, Assault on Dragon Keep; and Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel clearly aren’t a bonus, but a back-of-the-box feature. And I think a little close reading can show us how conservative and harmful messaging is laundered through these two characters and why distancing from these origins has been the best path forward for the series.

(Spoilers for the Borderlands franchise ahead)

One of the first things you hear at the start of Borderlands 2 are the smug, teasing words of Handsome Jack. Reminiscent of characters like Gordon Gekko and Patrick Bateman, he sprinkles a light dusting of truth on everything he says. He correctly diagnoses the problems of Pandora, the alien setting of Borderlands, as rampant with colonial violence while failing to see his part in it, going so far as to name himself the world’s hero. “Your family paid to be here,” Jack tells workers in a company town. “I’m the one who feeds and protects everyone! Remember, we should all love our parents, but love me more.” This is all well and good, until you notice the spotlight never really leaves him.

Borderlands 2 (and even more so The Pre-Sequel) is Jack’s story, and it pretty much can’t be helped that this edgelord who laughingly recalls blinding a man is written aspirationally. Since Borderlands wants to be funny, Jack is sold as an antagonist you “love to hate.” He embodies the popular myth of the self-made businessman. Like a venture-capital-funded Silicon Valley rockstar, he forcibly “disrupted” interstellar commerce with the innovation of orbital cannon delivery, repurposed alien tech into a Death Star-like weapon, and clawed—and strangled—his way to the position of President of the Hyperion corporation. You run across his girlfriend Nisha and learn that the series sexpot, Moxxi, is his ex. His alleged greatness even extends beyond the realm of the humanly possible. We learn that he is guided by visions of destiny, and that he is connected by bloodline to the incredibly rare group of superhumans known as Sirens through his abused and estranged daughter, Angel.

Jack’s writing is in keeping with the trend of edgy blockbuster games of the early 2010s like Far Cry 3, Grand Theft Auto V, and Bioshock Infinite, as well as chasing the popularity of “difficult men” from contemporary prestige TV, like Walter White and Don Draper. This empowered anti-hero narrative never really went away and has always struggled to justify itself, outside of assuaging Western culture’s guilt over maintaining its own hegemonic grip on power. With so much airtime spent on Jack, who mechanically serves only as a goalpost, you get the feeling he’s meant to be not wholly good or bad, but some centrist middle ground: a man who commits mass murder but has “good intentions.” The most telling revelations are the full details of his connection to Angel and his much-lauded efforts to save the lives of civilians on Pandora’s moon before his full Jokerfication. In the first example, Angel unintentionally killed her mother with her powers, which Jack deals with by locking her in a subterranean prison “for her own protection” as he tries to find a way to make money off her abilities. On the moon, he successfully stops the deployment of a WMD, but mostly for career advancement, sacrificing his co-workers’ lives in the process.

This wasn’t the only option, though. I’m a big believer in having your cake and eating it too when you’re worldbuilding from extreme privilege. Take General Sarrano, the antagonist from the Borderlands 2 contemporary, Bulletstorm (2011). Here we have a racist, sexist, militarist, and capitalist bootlicker who looks like his head was submerged in a deep fryer. In a stand-out mission, he murders your ally before tasking you with escorting him to deactivate a planet-scorching bomb. Along the way, he insults your combat abilities, cries for help when he’s surrounded, then curses you for not saving him faster. After he guides you through shutting off the bomb, he reveals you’ve instead just activated it and leaves you for dead! How Sarrano connects the heroes is entirely based on power—pitting them against each other while making their livelihoods dependent on him. He’s a truckload of edgy button-pushing and I hate him, and I love him. Most importantly, his cruelty serves the growth of the protagonists, bringing them closer together before they finally outright reject his nihilism by game’s end.

Borderlands 2 by contrast spends far more time on Jack’s pain, establishing him as the heart of the story. His losses, which are mostly fridged women with mere lip service paid to their tragic ends, are recalled as much, if not more frequently than those of the heroes. Not satisfied with this, The Pre-Sequel goes on to link Jack’s apathy to the betrayal of his trust by two more women (one being Lilith, more on her later), further cementing him as a tragic masculine figure. It’s as if someone on staff heard the phrase, “hurt people hurt people,” and took that to mean the most hurt person should then be the villain and dramatic center.

If the objective of Jack’s writing is about building sympathy for the devil, then Tina’s is about filtering who can and cannot “take a joke.” At a glance, Tina ostensibly exists like other characters to fill out the world and keep things light and fun. To fit the game’s aesthetic, she rocks a teen Tank Girl look and similarly speaks her thoughts out loud, usually in quips.

Her twee antics are further delivered when speaking with a Blaccent, referring to two explosives-stuffed rabbits as “fine ass womens” whose “badonkadonks…got stoled.” I expected to be annoyed on this return, but I wholly did not expect these racist asides. They have nothing to do with the train heist you plot with Tina and there’s few moments in Borderlands 2 that even compare. It’s a shockingly childish bit delivered by a literal child and the rhetorical game being played couldn’t be any more transparent.

After finishing Borderlands 2 I moved on to Assault on Dragon Keep, easily the most famous DLC in the franchise, proving to be a dry run before Tiny Tina’s Wonderlands released this year. Finishing it, what stood out most was how it absolutely goes “mask off” while escalating its harmful jokes. Taking inspiration from the Community episode “Abed’s Uncontrollable Christmas,” Dragon Keep has Tina lead the cast through a Dungeons & Dragons-like campaign. Together they fight wizards and knights while in the margins there are cues that Tina’s imagination is working to stomp down her grief over the loss of a friend. By the tearful end, her trauma is bursting at the seams and everyone reconciles. Except the story is not really about that, it’s about PC culture.

Between jokes about dice rolls, Tina spends much of the campaign making hedge arguments around what is and isn’t offensive. For example, Tina is called out by her friends for making all dwarves in the campaign resemble playable hero Salvador, who is Latino. Tina shouts to Salvador off-screen, asking if it’s OK, and we hear his response from another room saying it is, in fact, awesome. The biggest critic of Tina’s worldbuilding is Lilith, the de facto leader of the cast, who challenges her humor’s equal opportunity approach to offense. This backfires in Lilith’s face, casting her as a Joan Cusack-style fuddy-duddy type and “gatekeeper” against Tina’s free spirit.

Tina is presented as a chaotic figure of innocence that scoffs at convention only for her story to reaffirm conservative norms. So when the big emotional finale rolls along, the emotion is inert. Lilith and company’s criticisms of the game suddenly flip to Tina’s “correct” perspective, chalking up everything that’s come before as part of the healing process for her. It’s also a convenient way for the game to further indulge in status-quo affirming pap. It’s pretty rich that after calling out Lilith, and by proxy Borderlands 2’s critics, for assuming bad faith on Tina’s part, the story ends with a plea to please, think of the children!

None of this is to say the first Borderlands had no shades of reactionary writing. From the beginning, most of the fodder were “psychos” and “m*dgets” stylized as high school sketches. This couldn’t derail the game’s genuine qualities like its simplicity and ease of use allowing you to experience it at its best: converting grotesque humanoids into epic gear via comic violence. This tension carried over into the immediate sequels where player choice blossomed, the feedback for hot death diversified, all the while Pandora grew in beauty. The nadir also deeped as a creeping dread built whenever you approached a quest icon, knowing you’d be trapped in a one sided conversation with a clown. But the part we remember, the fun, was still alive under the clutter.

Consider Destiny (2014), released the same year as The Pre-Sequel; Bungie’s looter shooter owes a lot to Borderlands and confidently outclasses it in a couple ways while whiffing it in others. It presents its world with respect and mystery, promising discovery, and plays like, well, a Bungie game. At the same time, Destiny’s look can be described as lifeless with the faux, ageless architecture of a Starbucks. Moreover, it’s rife with obtuse menus, multiple currencies, and myriad proper nouns like Pomona Mons. The result is a seismic difference in user experience. A typical session of Destiny will have you checking in with multiple vendors only available at the hub to store, sell, or identify gear, grab some bounties to maximize your passive accrual of fun bucks, then be dropped off a good few minutes away from where you’ll be fighting ghosts…I think? The same for Borderlands amounts to picking a quest and/or location and fast traveling to the exact spot with vendors dotting the zone. Similar games like Warframe and The Division would continue to mistake the Nintendo-like pick-up-and-playability of Borderlands as just part of its cynicism and not what makes you—makes me—want to hit end credits.

Maybe I’m not as good at compartmentalizing the good from the bad as others and a little more work on my part could mean the difference between Skinner Box bliss and ear plugging frustration. But I maintain Borderlands didn’t have to resort to bad faith humor to hook its audience, and somewhere along the way they figured this out. The spinoff game, Tales from the Borderlands, casts the player as a Hyperion lackie who first idolizes Jack and upon meeting him can choose to challenge his views and even minimize his presence in the story. A just-announced sequel to Tales is promising a story with entirely new characters, all but certain to finally leave Jack behind. And while I haven’t yet played Tiny Tina’s Wonderlands yet, I’m hopeful that by doubling down on the D&D schtick, the game, and character, can leave her baggage in the rearview and chart a new story.

The direction the series wound up going was not obvious coming off the 2009 original nor was its commercial and pop success entirely a product of its own merits. A game crossing Mad Max with Diablo, supporting couch co-op, released on the heels of a once-in-a-generation recession? No wonder it made such an impact. As the coming decade looked bleaker than the last, friends and family could settle around the screen, grinding levels and riding off into the sunset, epic loot in hand. No “butt-stallion” required.

One thought on “Against Butt-Stallions”

Comments are closed.